1957 was a solid year for cinema, one where the medium seemed to be maturing in multiple directions at once. Hollywood was still capable of grand studio craftsmanship, but cracks were forming in the old narrative formulas that had dominated earlier decades. At the same time, filmmakers outside the US were pushing boldly into new philosophical, psychological, and existential terrain.

The titles below represent some of the most enduring classics to come out of that year. They cover a range of styles and tones, from bitter war dramas to pulpy sci-fi, character studies to ambitious Shakespeare adaptations.

10

‘The Incredible Shrinking Man’ (1957)

“I still exist.” ‘Although quaint and dated by today’s standards, The Incredible Shrinking Man deserves props for being an inventive, pioneering work of ’50s sci-fi, inspiring so many stories that would follow. (Without it, there is no Ant-Man, for example.) The premise is simple and entertainingly pulpy: ordinary man Scott Carey (Grant Williams) is exposed to a mysterious radioactive cloud and begins to shrink uncontrollably. As his body diminishes, his life collapses around him: his marriage strains, his independence vanishes, and he becomes trapped in his own home.

The plot escalates from social discomfort to outright survival horror as Scott is reduced to navigating a basement filled with everyday threats like spiders and falling debris, now rendered gargantuan in comparison to him. Most genre movies would stop there, but The Incredible Shrinking Man goes further, striving to be a little philosophical. Scott’s narration frames his physical reduction as a spiritual reckoning, forcing him to redefine his place in the universe.

9

‘An Affair to Remember’ (1957)

“If you can paint, I can walk.” An Affair to Remember is a finely crafted romance from director Leo McCarey, who worked on the likes of Duck Soup and Going My Way. This one follows Nickie (Cary Grant) and Terry (Deborah Kerr), two strangers who meet aboard an ocean liner and fall in love despite being engaged to other people. They agree to reunite months later at the top of the Empire State Building, believing fate will guide them back together. But when tragedy intervenes, misunderstandings and pride keep them apart.

Rather than being melodramatic, An Affair to Remember is sincere and restrained. It takes romance seriously, treating love not as infatuation, but as a commitment shaped by patience and sacrifice. It allows the emotion to accumulate slowly. The performances are fittingly measured, letting small gestures and pauses carry weight. All this builds up to a fantastical and memorable final act.

8

‘Nights of Cabiria’ (1957)

“Why do I have to suffer so much?” Nights of Cabiria is one of many masterpieces by the great Federico Fellini. It revolves around Cabiria Ceccarelli (Giulietta Masina), a small-time sex worker living on the outskirts of Rome, whose boundless optimism repeatedly collides with cruelty and betrayal. The plot unfolds episodically, presenting a series of encounters that test her spirit. Over the course of the story, she is robbed, humiliated, abandoned, and deceived, yet she continues to hope for love and dignity.

This could have been a grim morality tale or a didactic social commentary, but, instead, Federico makes it a compassionate character study. He refuses to mock or sentimentalize Cabiria, instead allowing her contradictions to coexist: toughness and vulnerability, cynicism and hope. The final scene, often cited as one of the most moving endings in movie history, crystallizes the film’s central insight: that endurance itself can be a form of grace.

7

‘Sweet Smell of Success’ (1957)

“I’d hate to take a bite out of you. You’re a cookie full of arsenic.” Sweet Smell of Success is a razor-sharp exploration of power and corruption. It’s set in the world of New York journalism and publicity, where a ruthless columnist (Burt Lancaster) manipulates careers and relationships at will. Opposite him is a desperate press agent (Tony Curtis) willing to destroy others to stay relevant. The plot revolves around a scheme to sabotage a young woman’s romance, becoming a showcase for ego, lies, and a toxic need for control. These were challenging roles to play, but all the leads do a fantastic job.

The tone is bleak and biting throughout, very much embracing the classic, cynical noir spirit. The dialogue is venomous, the atmosphere suffocating, and the characters almost entirely devoid of warmth. Success here is not glamorous but parasitic. At the time of its release, the film’s tone alienated audiences, but its vision now feels prescient.

6

‘Throne of Blood’ (1957)

“Ambition has made you drunk.” With Throne of Blood, Akira Kurosawa transposes Macbeth into feudal Japan, to phenomenal results. In it, a loyal warrior (Toshiro Mifune) encounters a prophetic spirit that ignites a hunger for power, leading him down a path of betrayal and violence. As he ascends the hierarchy, paranoia and fear consume him, his ambition and guilt becoming almost elemental forces. From here, the plot sticks closely to the structure of the original tragedy, but its expression is highly cinematic. Kurosawa replaces soliloquy with movement, fog, and silence, allowing atmosphere to convey internal turmoil.

Indeed, the visuals are striking throughout and rigorously composed. The stark landscapes and controlled performances create a sense of inevitability, as if fate itself is closing in. All in all, Throne of Blood serves as a great example of how universal stories can be reborn in new guises. It’s one of the very best adaptations of the play, which is saying something.

5

‘Wild Strawberries’ (1957)

“I feel as though I were dead, although I’m alive.” Wild Strawberries is Ingmar Bergman’s gentle meditation on memory, regret, and reconciliation with one’s past. It follows an elderly professor (Victor Sjöström) who embarks on a road trip to receive an academic honor, accompanied by his daughter-in-law (Ingrid Thulin). Along the way, he experiences vivid dreams and encounters that force him to confront unresolved guilt and missed opportunities. His journey in the present blurs with dream sequences and recollections.

His story feels remarkably emotionally honest. Here, Bergman treats aging not as mere decline, but as an opportunity for moral reckoning. Through the protagonist, the film asks whether self-awareness and compassion can still arrive late in life. It suggests, hopefully, that understanding and forgiveness are possible, even decades after the fact. These themes are universal, explaining why the movie influenced everyone from Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky to Federico Fellini and Satyajit Ray.

4

‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’ (1957)

“Madness! Madness!” Alec Guinness delivers a strong lead performance in this war epic, playing Colonel Nicholson, a British officer held in a Japanese POW camp during World War II. There, he and the other prisoners are forced to build a strategic bridge for their captors. The central conflict arises when Nicholson becomes obsessed with constructing the bridge as a symbol of discipline and superiority. Meanwhile, Allied commandos plan to destroy it. From here, the plot builds toward an explosive confrontation between principle and consequence.

Overall, The Bridge on the River Kwai stands apart from most WWII movies because it’s deeply psychologically complex. Rather than presenting clear heroes and villains, it explores how rigid adherence to honor can become a form of collaboration. The scale is epic, but the tragedy is personal. Along the way, the movie challenges simplistic notions of heroism, offering a sobering portrait of how easily integrity can become self-deception.

3

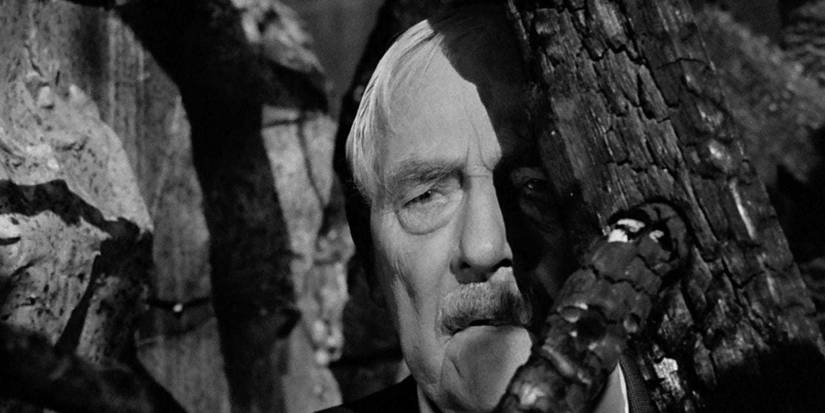

‘The Seventh Seal’ (1957)

“I want knowledge. Not faith, not assumptions.” Remarkable that Ingmar Bergman delivered not one but two classics this year. Set during the Black Plague, The Seventh Seal follows a disillusioned knight (Max von Sydow) who returns from the Crusades and challenges Death (Bengt Ekerot) to a game of chess, hoping to delay his fate while he searches for meaning. As the journey unfolds, the knight encounters performers, peasants, and victims of plague, each embodying different responses to suffering and uncertainty.

In other words, the narrative is structured around philosophical encounters rather than traditional action. All of this serves to explore ideas of faith and mortality. Here, Bergman transforms abstract questions about God and death into striking images and human interactions. Few directors have articulated doubt with such beauty and honesty. Taken together, The Seventh Seal is a powerful statement on the timeless human struggle to find purpose in a seemingly indifferent universe.

2

‘Paths of Glory’ (1957)

“There are times when I’m ashamed to be a member of the human race.” Paths of Glory is a lean, mean masterpiece from Stanley Kubrick, a potent war drama that also functions as an indictment of military hierarchy and institutional cruelty. It unfolds during World War I, revolving around a group of French soldiers ordered into a suicidal attack, then court-martialed for cowardice when the mission inevitably fails. Kirk Douglas leads the cast as the colonel who attempts to defend his men against a rigged trial designed to protect superior officers.

Some critics have argued that there are no true anti-war movies, but Paths of Glory certainly comes closer than most. In it, Kubrick strips war of nobility, portraying it as a system that sacrifices individuals to preserve authority. The trench warfare sequences are claustrophobic and terrifying, while the courtroom scenes expose the emptiness of bureaucratic justice. The whole thing practically shakes with moral outrage.

1

’12 Angry Men’ (1957)

“It’s not easy to raise my hand and send a boy off to die without talking about it first.” Perhaps the finest courtroom drama ever made, 12 Angry Men transforms a single room and a simple premise into a gripping moral exploration. The setup is iconic, almost elemental: twelve jurors are tasked with deciding the fate of a teenage boy accused of murder. An initial guilty vote seems inevitable, but one juror (Henry Fonda) calls for more discussion. The drama unfolds entirely through dialogue and shifting dynamics, as certainty gives way to doubt.

Rather than action or theatrics, Sidney Lumet uses blocking and camera movement to intensify tension, turning this confined setting into a psychological pressure cooker. The jurors’ exchanges gradually expose prejudice, flawed reasoning, and personal bias, raising questions about responsibility, empathy, and the possibility of certainty. Released during a period of social conformity, the film championed individual conscience against collective haste, and its message continues to resonate today.

Source link