‘The Sinner,’ Vatican terms, and stretching curds

Hey everybody,

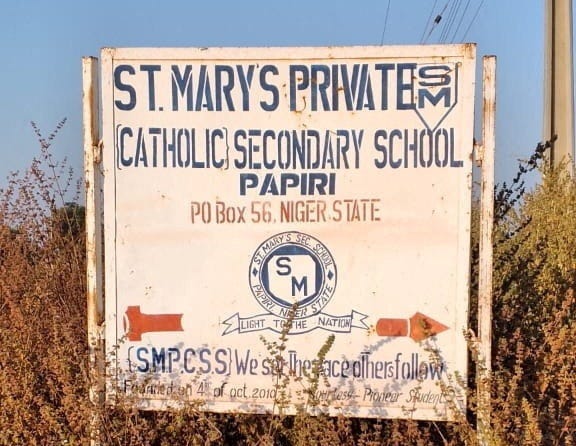

Before anything else, take a minute to pray this morning for 253 students and 12 teachers who were kidnapped last Friday from St. Mary’s School in Papiri, northwestern Nigeria.

In fact, more than 300 students were kidnapped last week, but 50 managed to escape their captors late Friday night, and to run home. The students are between 12 and 17 years old. Most of them live at the school — and were taken by force from the dorms where they lived.

They were kidnapped, according to a local bishop, by an organized and violent criminal gang — ransom kidnappings are common in the lawless parts of north and central Nigeria, and kids at a boarding school likely present a target of opportunity.

But they have no idea if their children will ever be coming home. While we’re preparing for Thanksgiving, these families are likely in real despair — and they’re our brothers and sisters in Christ.

Let’s actually pray for those families, for those children, and for the teachers trying no doubt to keep them calm. And let’s pray for the future of Nigeria — a generation which has endured what these children will endure will no doubt need prayers for the whole of their lives.

—

Now, when you celebrate Thanksgiving on Thursday, take a minute to ask for intercession of St. Jacob Intercisus, a fifth-century Persian martyr whose feast is on Thanksgiving this year, November 27.

Jacob was a soldier in the Sasanian Iranian empire, which ruled a big swath of Asia for a few hundred years, from the third to the seventh century.

Jacob wasn’t just a soldier. He was a close confidante of Emperor Yazdegard I, about whom we know very little, except his nickname: “The Sinner.”

But really, if you’ve got a nickname like that, I think we’ve got the picture pretty clear.

Jacob was also a Christian. And, it turned out, a coward — a chicken, if you will — at least at first.

See, at first, Yazdegard — “The Sinner” — was cool with the Christian communities scattered across his empire — they paid their taxes, they didn’t war with anybody, and, despite his many sins, they prayed for him.

But the aristocratic Zoroastrians of the empire didn’t like Yazdegard’s tolerance of Christians. They turned against him — and when a king loses the nobility, it’s often just a matter of time before he loses his throne, or his head.

Yazdegard eventually did what he could to appease the Zoroastrians, which meant that he started persecuting Christians — arresting them, torturing them, and having them killed, for failing to observe the official Zoroastrian rites of the Empire.

That put Jacob in a bad position. He was a Christian. His family was Christian. If he identified himself as such, he’d lose the friendship of Yazdegard, his positions in the empire, and maybe his life.

So he apostasized; told Yazdegard he wasn’t a Christian at all. And kept his head.

But Jacob watched the persecutions around the empire continue. He watched people he loved put to death. And he couldn’t look his family in the face. Let alone pray.

He was filled with regret and sorrow.

The persecution didn’t work out for Yazdegard, either. He was killed in 420 by Zoroastrian nobles.

Soon after, Jacob went to the new emperor — Bahram V — and declared his Christianity. He had to do it. His conscience didn’t allow him to hide out.

Bahram — supported by the Zoroastrian nobles — had big plans for Christian persecution (which would lead to a brief war with the Christian Roman empire).

Jacob himself was arrested. But because of his status, he was given ample opportunity to deny the Christian faith. Along the way, he was tortured.

First some fingers were cut off. He did not deny Christ. Then his toes. He did not deny the Lord. Then his arm, at the elbow. He did not recant.

Then both arms lopped off at the shoulders. He survived, and he did not deny Christ.

At that point, you’d have to figure Jacob was all in — if he was going to recant, he’d do it before the arms went, not after. Otherwise, he’d be looking at a life without arms in an empire without sterile gauze pads. And if James Garfield died just 145 years ago from incompetent, infection-spreading medical care — after a relatively benign gunshot wound — you’ve got to figure Jacob’s chances after the armectomies would be pretty slim.

Still, there was a crowd watching the torment, begging Jacob to deny Christ. But he wouldn’t do it.

And so the last thing he lost was his head — Jacob, first an apostate, died a martyr for Christ.

—

If you read Latin, you’ve already worked out the name by which he is remembered — Intercisus means “cut into pieces.”

And it just so happens that his feast is on Thanksgiving this year, when you’ll be carving a turkey.

I don’t regard it too grim or morose if you remember then St. Jacob — the-chicken-turned-martyr — and ask for his intercession.

It seems almost rude not to.

Pope Leo on Friday held a “virtual encounter” with American teenagers, in which the pope warned strongly that technology, especially AI, can pose a threat when it replaces and weakens genuine human connection.

“Simple things — a hug, a handshake, a smile. All those things are essential to being human, and to have those things in a real way, not through a screen,” the pontiff told them during a video dialogue from Rome to the National Catholic Youth Conference.

“Be careful that your use of AI does not limit your true human growth. Use it in such a way that if it disappeared tomorrow, you would still know how to think, how to create, how to act on your own, how to form authentic friendships,” the pontiff added.

Here’s what he said.

—

After the pope’s talk, our own Jack Figge asked the young people present what they thought about their virtual encounter with the pontiff.

Most of them said it was a meaningful moment — and that “it felt pretty real” for a video conference call.

Here’s what participants and organizers had to say.

This Advent, gather with fellow Catholics for a Bible study unlike any other. Bible Across America is a nationwide Bible study hosted by the St. Paul Center. During this inaugural study, we’ll encounter Christ as “Teacher and Lord,” discovering what this means for our lives as modern-day disciples.

Meanwhile, Pope Leo XIV called for renewed commitment to ecumenism among Christian denominations on Sunday, urging all Christians and their leaders to deepen their communion in the commonly confessed tenets of the faith.

In an apostolic letter released ahead of a papal trip to Nicea — during which Leo will join the Patriarch of Constantinople to mark the 1700th anniversary of the ecumenical council which produced the eponymous creed — Leo recalled the bitterly divisive doctrinal disputes which preceded and followed the formulation of the Nicene Creed.

He called for an ecumenism that focuses less on ancient theological controversy, and more concretely on a “common understanding and even more, a common prayer to the Holy Spirit, so that he may gather us all together in one faith and one love.”

So what’s the state of ecumenism today — especially with the Orthodox Churches to whom the pope seemed to be speaking? Ed Condon breaks it down.

—

Members of Germany’s interim synodal committee finalized the statutes of a new national synodal body Saturday, in the first major step toward creating the permanent structure envisaged by the country’s synodal way.

That process has not been without controversy. But it is set to play a major role in German Church affairs for years to come — and from Germany, in places across the world.

Assuming, of course, that the Apostolic See approves the statutes. And while the Germans have made efforts to allay concerns from the Holy See, nothing is written until it is written.

So what’s the state of play? Luke Coppen reports.

—

Anglican clergy are continuing to join the Catholic Church in the U.K. following spikes in receptions in 1994 and 2011, according to a new study.

In fact, more than 700 Anglican clergy and religious have become Catholic since 1992, including 16 Anglican bishops.

Here’s the situation.

—

And The Pillar debuts a new regular columnist this week, as Simcha Fisher does what she does best — unpacking the source of “balance” in the Christian life, and putting together a good recipe for pie.

Finally, the Apostolic See promulgated updated regulations Sunday for personnel in the dicasteries and offices of the Roman curia — think of the text as the employee handbook of the Vatican.

The curia — if you need a reminder — is running an eight-figure structural budget deficit, and laboring under a giant pension deficit and a basic problem with spending more than it takes in each year.

Fixing that problem will be among the biggest administrative tasks Leo faces in his papacy — even if, to date, he’s tried to give the impression that the problem is not as big as the numbers suggest.

But a very basic perusal through the employee handbook at the Vatican reveals a commitment that should be imitated at every level of ecclesiastical life, if you ask me: The urgent need to balance the budget has not left employees holding the bag.

Their pay could be higher at the Apostolic See, as employees there mention, often. But there are benefits embedded in the Vatican employee policies which are worth noting.

Article 60 of the new regulations details, for example, maternity leave policies at the Roman curia, which include an effective 6-month maternity leave at full pay — either the last trimester and the three months after birth, or, if needed, the last month before birth, and then five months thereafter.

That period is followed by another period of time, until a child turns one, when a nursing mother can reduce her workday by two hours, and then the prospect of taking off up to six months before a child turns 3, with 50% pay for that entire time.

Now, I run a business in America, and I can see already that a policy like this is both well beyond what most Americans are accustomed to, and potentially quite expensive, if mothers on long periods of leave need to be temporarily replaced by other employees. At The Pillar, we give a just and lengthy maternity leave, but at parishes and chanceries, it’s often a different story.

But the Roman curia, operating in the sovereign state of Vatican City — a vassal state of the Holy See — can pretty much do what it wants with labor law, and chooses this policy for a reason that seems worth noting: Because it can, and, as it perceives things, it should, regardless of the cost.

It has a budget to balance, but employees — and families — seem still to have dignity.

As it happens, Catholic institutions in the United States have fairly broad latitude with employment policy as well, which means that a policy like this is worth talking about: If the pope’s own employees can take a real and lasting maternity leave, shouldn’t mothers here expect the same thing?

Especially since some U.S. dioceses are (for the moment) slightly less broke than the Apostolic See.

—

But while I’m praising Vatican maternity leave, a friend of mine pointed out in these regulations an embedded issue that makes working with the Vatican a challenge for dioceses across the world.

It’s a presumption, really, but one worth noting.

While a broad swath of roles in the Roman curia have become open to laity and non-clerical religious, there are still plenty of jobs which require the power of orders — namely, the power of governance conferred at ordination. For that reason, the Vatican is and remains a highly clerical workplace, and it would be folly for it to be anything else.

But the regulations serve as a reminder that most clerics who go to work in the Roman Curia — the civil servant class who do the actual work — are short-timers. The regulations emphasize that the ordinary term of service in the Vatican for clerics and religious is five years, which is then “possibly renewable.”

They say this for a few reasons, but one of which is that Rome is always working very hard to find bishops who will agree to let their men serve important desk jobs inside the apparatus of the Vatican. It’s much easier to get a bishop to agree to send a man for five years than it is to see him sign off on a life in Rome.

So, the bishop is told, “your guy will be gone for just five years — maybe 10 at most — but when he comes back he’ll know everything about how the Vatican works, which is good for the diocese — and besides, he can get a doctorate while he’s over here and then come back and teach in your seminary.”

The problem, as anyone who has spent time in Rome knows, is that it takes almost a full five years to understand how the Italian bus system works — when you have to pay and when you can wing it — and a lot more than five years for most people to feel confident driving in Bella Roma.

The Eternal City measures time in centuries, which means that five years isn’t a very long span to learn the place, or its people. And 10 years is enough time to learn the contours and responsibilities of a job in the Roman curia, but maybe not long enough to acquire wisdom in doing it.

To be sure, there are plenty of bishops willing to let their guys stay on in Rome for more than a pair of terms, but Vatican short-timers fill a lot of jobs. And when important dicasteries experience almost complete staff turnover inside of a decade, it presents a challenge for everybody.

Changing the terms just slightly could make a big difference. If Vatican staffers were sent to work for seven years, two terms would be 14 — time enough to have got good at the job, and possibly enough time for the home diocese to realize they don’t need the man to hurry back as fast as they thought anyway. If a man could get 21 years of Vatican service with just three assents from his bishop, instead of four, turnover might cut down quite a bit.

And while service in the Vatican is a tough way to live a priesthood, those clerics willing to do it for 21 years or longer are of immense importance to the governance of the entire Church.

There’s something biblical about seven-year terms, anyway. Creation is on a seven-day cycle, Joseph prophesied in seven-year cycles, and, perhaps most relevant, Jacob labored for Laban seven-year stints.

Of course, Jacob married a dull cousin after his first seven-year term, and then her lovely sister seven years later — so perhaps we oughtn’t take the analogy quite that far!

Still — the Labanite sisters aside, a seven-year term could be a game-changer in the Roman curia. Should Leo eventually go in this direction, you’ll know where he got the idea. Even if a generation of clerics in Rome, ready to come home, might prefer wrestling an angel.

I wasn’t sure this week whether I’d have for you a tale of defeat or triumph.

I won’t actually know until Thanksgiving Day.

See, a few weeks ago, I got the idea that I should like to bring something new for Thanksgiving day at my sister’s house: Kate usually contributes some desserts, and usually I bake a bunch of bread.

But I wanted to do something different. And then I realized what it should be: I wanted to make cheese. It was finally time.

Years ago, I was on a bus in rural Poland, traversing mountain switchbacks in the Carpathians, on narrow roads a large tour bus had no business being on. I’m not sure how the system worked, but the roads must have been designated “one way,” because there was simply no room for opposing traffic on most of these rutted tracks, at least as I recall it.

We whizzed by rural villages at breakneck speed — I’ve long suspected the driver was regretting a Big Gulp or something and had to get to the bathroom — and by small farmhouses, where people kept ponies, and sheep, and a cow or two, in much the same manner their families had done for generations, hopefully hiding out in those mountains from the schemes and bad architecture forced on Poles by the cartoonishly evil communists down in Warsaw and Krakow.

The houses have satellite dishes now, and rusting out old cars on blocks in the front garden, but still, you could see that a way of living was being preserved — not self-consciously at all, as old people sat on porches preparing dinner and chain-smoking, and little kids ran under their feet.

I was intrigued especially by the little pallet shacks put up on many farmyards, and by the big iron vats people stood stirring over open fires, leaning forward with mixing paddles and dangling ashy cigarettes right into cauldrons.

Watching for a while, I realized they were making cheese: sourced from their own milk, probably, cooked in giant pots, and stretched and smoked on racks inside the makeshift buildings. Nothing about the process struck me as especially sanitary —- the curds were ashed with a steady stream of Turkish tobacco, and the treated lumber of the shacks’ walls almost certainly leached noxious chemicals right into the cheese.

But the whole thing seemed deeply beautiful, and more important, just a whole lot of fun.

So I have harbored since then aspirations of hobby cheesemongering. When other men talk about their pellet food smokers and brining briskets, I’ve thought about a little cheese cave off my basement, where I’d put up Camemberts and Stiltons to age and mold in just the right conditions.

My wife points out that the cats’ litter box is in the basement, which makes it unsuitable for cheese-caving, and she’s right of course, though I bet they’re not deterred by such things up in the Carpathians.

Anyway, I decided to start this year with an easily made and easily stored mozzarella, which would require no aging, and might be a fun project for the kids.

I pictured a lively afternoon of stretching shiny curds into cheese, all of us laughing, in Christmas sweaters of course, even if none of us were dangling ashes over the cauldron.

I spent a few weeks reading recipes online, and I briefly visited the obsessive and cutting cesspool of cheesemaking reddit. I even learned why some romance languages use words like formaggio or fromage for cheese, while Spanish uses “queso,” linguistically related to our own “cheese” and the German “käse.” (It all has to do with Roman military history, believe it or not.)

Anyway, after much reading, I ordered my supplies, sourced from a couple of cheesemaking online writers I’d come to trust.

It was time.

Of course, the best cheese is made with raw milk, as fresh as can be, because of something about the pH, and the high fat ratio, which gives you higher yields per gallon, and possibly curds that are easier to work with.

I spent a couple of days trying to source raw milk — I never felt more like an aspiring homeschooler — and my dad even drove down to a dairy farm in rural Colorado, but we learned that in our state, (where psychedelic mushrooms can be found in stores, and mescaline is almost a rite of passage), unpasteurized milk is regarded as just too dangerous.

You’d hate to be stoned out of your mind on perfectly legal hashish, chowing down on THC cookies, and accidentally drink some microbes in your milk, after all.

So, fool that I am, I figured if I couldn’t have raw milk, organic was the next best thing. I bought a gallon at the grocery store, paying almost seven bucks, and set it to heat in my dutch oven.

Source link