Hakeems believe they are the only practitioners consistently working in far-flung regions, noting that MBBS doctors, even those from rural backgrounds, rarely practise in their native areas.

When Arsalan Ali walks into his classroom, he is no longer sure whether the degree he is working towards will exist by the time he graduates.

He’s a trained pharmaceutical chemist with an MPhil degree who used to work in the allopathic drug business. Over time, however, he grew disillusioned with what he describes as the “side effects of modern medicines” and turned instead to traditional healing.

He, therefore, enrolled for the Fazil-i-Tibb-wal-Jarahat qualification, hoping to practise Unani medicine.

Fazil-i-Tibb-wal-Jarahat is a government-recognised degree that trains practitioners in Unani medicine, a tradition of healing that has been practised in South Asia and modern-day Central Asia for hundreds of years. It is a healing system that employs herbal remedies to maintain a balance of bodily temperaments, based on Greek, Persian and Arabic influences.

Currently enrolled at a tibb college in Lahore, Ali says recent developments have left students like him questioning whether their education will mean anything in legal terms.

“I have come to know that a new legislation has been proposed, due to which not only will my college be closed in a few years, but there will be a question mark on my degree and licence to practice,” he said while talking to Dawn.

The government has recently instructed colleges not to induct new students from the next academic session, giving rise to fears that the proposed merger of the National Council for Tibb and the National Council for Homoeopathy will lead to the closure of institutions that have trained traditional hakeems for decades and leave thousands of practitioners, many of whom are serving rural and low-income communities, without legal recognition.

The fears have become more intense after the health ministry moved to “right-size” its regulatory bodies through an Act of Parliament.

Practitioners say the decision places more than 70,000 hakeems holding the Fazil-i-Tibb-wal-Jarahat qualification at risk of losing their livelihoods and could result in the closure of all 40 tibb colleges currently operating across the country.

According to college administrators, these fears are not speculative but rooted in official instructions already issued by the government.

Professor Imran Lodhi, principal of Rawalpindi’s Ajmal Tibbia College, explained that traditional medicine operates within a distinct legal and educational framework that is at risk of being erased by the proposed merger.

“There are mostly three types of healthcare practitioners in Pakistan, i.e. allopathic, homoeopathic, and hikmat,” he said while talking to Dawn.

Outlining the regulatory distinction underpinning each system, he said that while allopathic practice is being done under the Drug Act 1976, hikmat is being carried out under Pakistan’s Unani, Ayurvedic and Homoeopathic Practitioners Act, 1965.

“Under the Act, regulatory councils, including the National Council for Tibb and the National Council for Homoeopathy, were established,” he said.

Professor Lodhi added that the education pathways for tibb students were already structured and regulated, as there were 40 colleges of hikmat and 140 homoeopathic colleges functioning across the country.

“Hakeems believe they are the only practitioners consistently working in far-flung regions, noting that MBBS doctors, even those from rural backgrounds, rarely practise in their native areas.”

Pakistan Tibbi Alliance General Secretary Hakeem Muhammad Sajjad has formally raised these concerns with the ministries of health and law. In letters, he has urged the government to halt consideration of the draft legislation.

He said the draft law, titled the “National Traditional and Complementary Medicine (NTCAM) Act, 2025”, contains serious gaps that could dismantle the sector.

According to him, the proposed changes stem from broader fiscal reforms driven by international commitments.

“As per the recommendations of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), all the ministries and divisions have been taking steps for right-sizing,” Professor Lodhi added.

Last year, Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb said the government planned to abolish 150,000 posts as part of IMF-backed structural benchmarks.

From Lahore, Hakeem Sajjad pointed out that the financial burden of the councils was “minimal” for the government, questioning the logic behind their merger.

Other practitioners warned that the merger could make practice itself impossible.

“It is unfortunate that there are so many departments, which have been using tens of millions of rupees from the exchequer, were ignored, and two councils, which hardly get any amount from the exchequer, are being merged,” said Hakeem Sarfarz Bhatti from Gujranwala.

A senior health ministry officer, speaking on condition of anonymity, acknowledged the policy’s risks but said officials had little room to manoeuvre.

“We know that the decision will create a huge vacuum and administrative issues, but we are helpless. Merging both councils is similar to mixing black tea, coffee and green tea, as their scope and nature of work are different.

He added that internal disagreements between practitioners would further complicate the plan.

“Hakeems and homoeopathic doctors don’t recognise each other, so how will they be placed under one umbrella?” he said.

The health ministry, however, maintains that the process is consultative. According to spokesperson Sajid Hussain Shah, the merger aims to improve standards.

Akin to practitioners, students have expressed experiencing similar anxiety.

Sameera Kamran, a student at the Ajmal Tibbia College in Rawalpindi, told Dawn that she enrolled believing that tibb colleges offered an affordable path into healthcare, especially for those from lower-middle-income backgrounds. That belief, she said, had now been shaken.

“Annual fees at colleges ranged between Rs 35,000 and Rs 40,000, compared to medical university fees that could be up to five times higher,” she said.

Ijaz Ahmed, a fourth-year student from Narowal, agreed, saying tibb colleges remained the last viable option for many families.

“We have been paying Rs 300,000 for the entire course in colleges, but in universities, students will have no choice but to pay over a million rupees. The government’s move will close the doors to hikmat and shatter students’ dream of becoming tabeebs, especially those who belong to the lower middle class,” he said.

Both students also agreed that rural healthcare would suffer because of the decision.

“The majority of the basic health units (BHUs) in rural areas lacked doctors. So hakeems are providing treatment to the masses. There will be no one to take care of them if colleges are closed,” said Ahmed.

For students like Arsalan Ali, however, the debate remains deeply personal. He says his decision to study tibb was rooted in belief as much as career planning.

“I had decided to return towards the nature as there was a remedy for every disease in herbs. However, after spending over three years, I have been facing uncertainty regarding my future. I fear that soon the name of Tibb-i-Unani (Unani Medicine) will be eliminated from Pakistan, and medicines prepared by different companies will be sold,” he said.

He pointed to neighbouring countries where traditional medicine is actively promoted.

“On the other hand, that business is not only flourishing in India and China, but they have been earning a huge amount of foreign exchange from it. The traditional Chinese medicine is made under the theory of ‘Ying and Yang’, which refers to wood, fire, earth, metal and water,” he explained.

Ali added that Unani practice relies on individualised treatment.

“A number of books regarding human temperament were used by Hakeems, and they prescribe different medicines to different patients having the same complaint,” he said.

Patients, too, share stories of reliance on traditional medicine. Awais Siddique, a Lahore resident, recalled seeking help for his wife after exhausting hospital options.

“I had a baby boy after three years of my marriage, but after that, my wife started getting sick. At that time, I was residing in Sheikhupura, so I took her to the hospital, and they gave her some of the medicines due to which my wife started feeling a bit better,” he said.

He said her condition worsened after their second child.

“Later, she was diagnosed with bone marrow cancer, and doctors suggested taking her to Rawalpindi. But they informed me that the bone marrow transplant would cost me Rs7 to Rs8 million. On the other hand, my wife frequently required three to four units of platelets. It was impossible for me to arrange such a huge amount,” he said.

Turning to a hakeem was a last resort, he said.

“So, I went to a hakeem’s clinic, who prescribed three months of medicine, and just after two weeks, my wife’s platelets reached 150,000,” he claimed.

Siddique said the treatment brought “lasting relief”.

“After three months, hakeem sahib told me that my wife would never face the same issue and does not require medicine anymore. She has been healthy for the last two and a half years,” he claimed.

According to the Cancer Research Centre UK, there is no scientific evidence that traditional or homoeopathic treatments can prevent or cure any type of cancer.

Amid the increasing pressure, representatives of the Pakistan Medical Alliance met government officials earlier this month. A delegation, including Hakeem Sajjad, Professor Lodhi, and principals of leading Tibb colleges, held meetings with the Minister of State for Health, Malik Mukhtar Ahmed Bharat, as well as senior officials at the health ministry and the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (Drap), to discuss the survival and protection of the Unani, Ayurvedic and Homoeopathic Practitioners Act, 1965.

Until clarity emerges, students like Arsalan continue attending classes with no assurance that the system training them will still exist when they step out to practise.

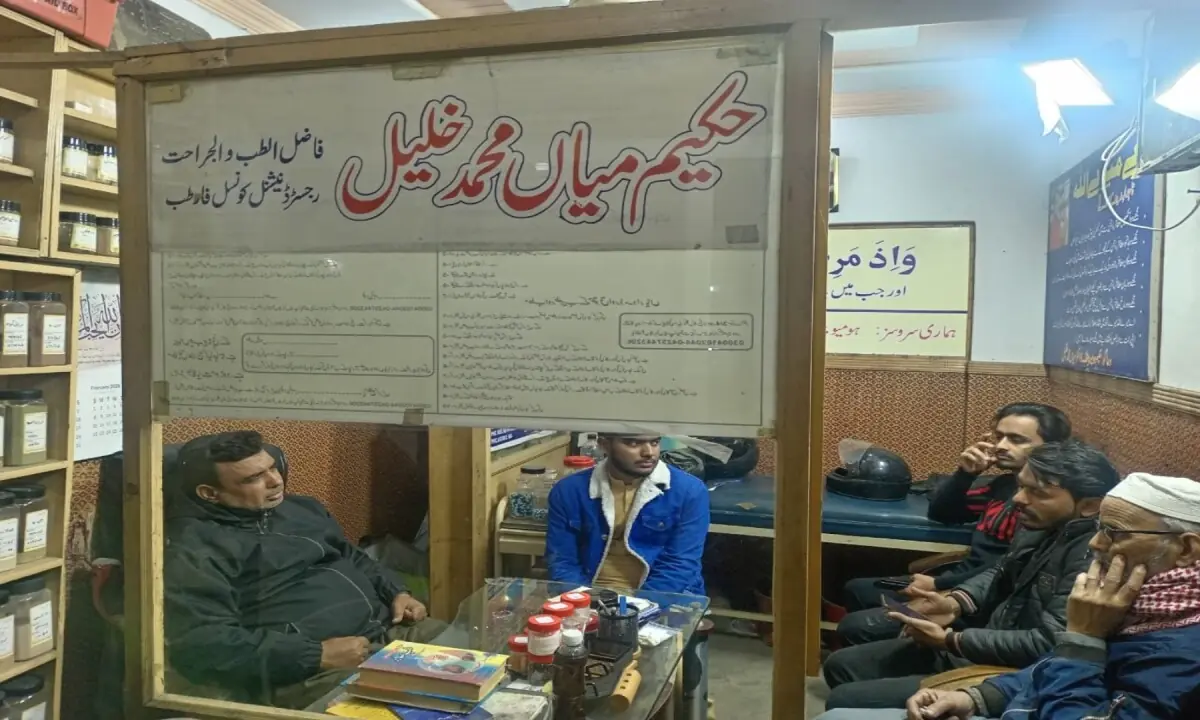

Header image: People sitting at the clinic of Hakeem Ishaq Sultan in Lahore. — Ikram Junaidi

Source link