This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson from the Yale School of Medicine.

About a year ago, I was talking to one of my friends about the slew of studies showing very broad benefits of the GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as semaglutide (Ozempic) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro). including weight loss and improved diabetes control. But studies also showed improved heart and kidney health, as well as lower overall mortality. Some analyses found reductions in problem drinking, smoking, and even compulsive shopping among people taking these drugs. I told my friend that I thought these drugs were complete game changers, fundamentally “anticonsumption” agents that are the cure for society’s primary ill of overconsumption.

“Yeah, but what about the side effects?” he said. I said, “Sure, some gastrointestinal issues can come up, but usually it’s not that bad.” Still, I demurred, “It’s early days; perhaps after 10 years on the drugs your eyes fall out or something.”

This week’s study doesn’t suggest that GLP-1’s cause your eyes to fall out exactly, but, as you’ll see in a second, it’s not that far off.

We’re talking about this study, “ Semaglutide or Tirzepatide and Optic Nerve and Visual Pathway Disorders in Type 2 Diabetes,” appearing in JAMA Network Open, which looks at eye problems in people taking the two most potent GLP-1 drugs.

This was a huge retrospective cohort study using the TrinetX database, which contains electronic health record data on millions of patients across the United States.

Researchers identified more than a million individuals with diabetes in the database who had no history of eye disease. They then identified when they were first prescribed Ozempic, Mounjaro, or a bunch of non-GLP-1 diabetes medications (such as insulin and metformin) which serve as controls here.

They were on the lookout for conditions that some smaller studies had suggested might be associated with the weight-loss drugs: disorders of the optic nerve — in particular, a rather rare condition that can occur even outside diabetes, known as non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION). This is a syndrome caused by a decline in blood supply to the optic nerve and is characterized by the sudden and painless loss of eyesight in one eye, which can lead to permanent blindness.

It seems straightforward to ask which group — those who got the GLP-1 drugs or those who took other diabetes drugs — had more eye problems. But you probably suspect that these two groups weren’t exactly comparable even before they started the drug.

People who took weight-loss drugs were younger, more likely to be female, more likely to be on antihypertensive drugs, more likely to have a history of sleep apnea, and much more likely to have obesity.

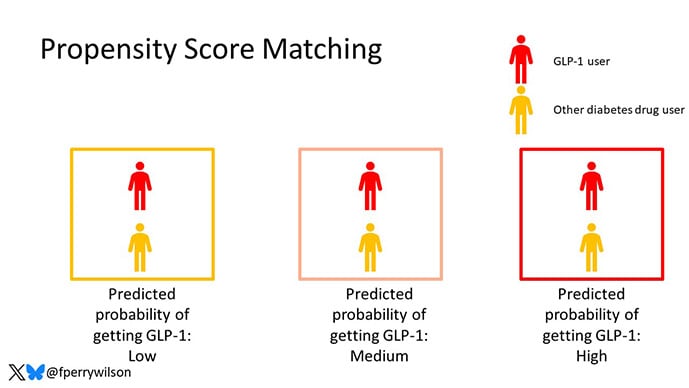

This is a classic apples-vs-oranges problem in observational research, one that was overcome, in this case, through a form of statistical wizardry called propensity score matching. In this process, each patient is assigned a likelihood of being prescribed the weight-loss drug, and then they are matched with someone with similar propensities. Thus, only one of each pair actually received the drug.

Naturally, not everyone was matched; the apples and oranges that were just too appley or orangey were dropped from further analysis. After matching, the two groups were much more similar.

Now that we have two similar groups — one of orangish apples and the other of appley oranges — we can compare the rates of NAION between them.

Of 79,699 individuals started on either Ozempic or Mounjaro, 35 developed NAION within 2 years of follow-up. Of 79,699 started on non-GLP-1 diabetes drugs, 19 developed NAION over a similar duration of follow-up. That’s 0.04% compared with 0.02%.

There are a couple of ways to look at the data. On the relative scale, we see nearly a doubling of the risk for this eyesight-threatening disorder among people taking GLP-1 drugs. But on the absolute scale, any given individual’s chance of actually getting this disorder is vanishingly small; the rate in the GLP-1 group was 462 per million individuals, compared with a baseline rate of about 238 per million individuals.

Identifying rare risks like this is still important, especially for drugs that are as widely prescribed as the GLP-1’s. Patients and providers need to have this in the back of their minds so that, if an unusual eye symptom does develop, everyone can react quickly.

It’s still not clear how these drugs could lead to NAION. It’s true that the optic nerve has GLP-1 receptors on it, so this could be a direct drug effect. But the researchers suggest other possibilities as well, including the idea that sudden metabolic changes associated with weight loss or glucose effects from the drugs may change the microenvironment of the eye. I hate to fall back on “more research is necessary,” but the truth is, more research is necessary to figure out how this works and, importantly, who is most at risk.

I should remind you that this study shows us correlation, not causation. Even with propensity score matching, there will still be differences between the comparison groups that aren’t fully accounted for.

Beyond that, the very fact that people may be on alert for eye disorders among those taking GLP-1’s may become something of a self-fulfilling prophecy in a study like this. If physicians are primed to think of a rare diagnosis like NAION when they see a patient on a GLP-1 drug, they might be more likely to make the diagnosis than they would if presented with exactly the same symptoms in someone not taking the drug. When the outcome is rare like this, minor biases can drive the results.

So, I’m not ready to go back on my statement that these drugs are game changers. They clearly are. But we’d be naive to assume that there wouldn’t be some risk. I’m encouraged that this particular risk is not nearly of a magnitude and frequency to counteract the obvious benefits of the drugs. In the end, this is one of those knowledge-is-power things. I don’t think we’ll see enthusiasm dampen for the GLP-1 drugs because of NAION, but it doesn’t hurt for any of us — patients or providers — to be aware of it.

Source link