Sakshi VenkatramanUS reporter

Kaaviya Sambasivam/Simone Mckenzie / Google Veo 3

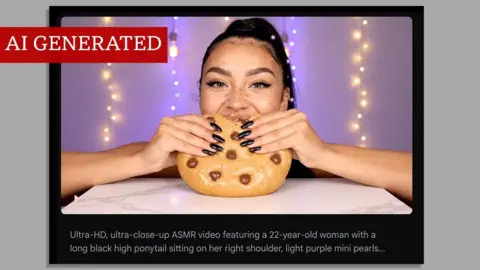

Kaaviya Sambasivam/Simone Mckenzie / Google Veo 3In some ways, Gigi is like any other young social media influencer.

With perfect hair and makeup, she logs on and talks to her fans. She shares clips: eating, doing skin care, putting on lipstick. She even has a cute baby who appears in some videos.

But after a few seconds, something may seem a little off.

She can munch on pizza made out of molten lava, or apply snowflakes and cotton candy as lip gloss. Her hands sometimes pass through what she’s holding.

That’s because Gigi isn’t real. She’s the AI creation of University of Illinois student Simone Mckenzie – who needed to make some money over the summer.

Ms Mckenzie, 21, is part of a fast-growing cohort of digital creators who churn out a stream of videos by entering simple prompts into AI chatbots, like Google Veo 3. Experts say this genre, dubbed “AI slop” by some critics and begrudging viewers, is taking over social media feeds.

And its creators are finding considerable success.

“One video made me $1,600 in just four days,” Ms Mckenzie said. “I was like, okay, let me keep doing this.”

After two months, Gigi had millions of views, making Ms Mckenzie thousands through TikTok’s creator fund, a programme that pays creators based on how many views they get. But she’s far from the only person using AI to reach easy virality, experts said.

“It’s surging right now and it’s probably going to continue,” said Jessa Lingel, associate professor and digital culture expert at the University of Pennsylvania.

Its progenitors – who now can generate videos of literally anything in just a few minutes – have the potential to disrupt the lucrative influencer economy.

But while some say AI is ruining social media, others see its potential to democratise who gains fame online, Lingel said. Those who don’t have the money or time for a fancy background, camera setup or video editing tools can now go viral, too.

Simone Mckenzie / Google Veo 3

Simone Mckenzie / Google Veo 3Traditional influencers being pushed out?

Social media influencing only recently became a legitimate career path. But in just a few years, the industry has grown to be worth over $250bn, according to investment firm Goldman Sachs. Online creators often use their own lives – their vacations, their pets, their makeup routines – to make content and attract a following.

AI creators who can make the same thing – only faster, cheaper and without the constraints of reality.

“It certainly has the potential to upset the creator space,” said Brooke Duffy, a digital and social media scholar at Cornell University.

Ms Mckenzie, creator of Gigi, said videos take her only a few minutes to generate and she sometimes posts three per day.

That’s not feasible for human influencers like Kaaviya Sambasivam, 26, who has around 1.3 million followers across multiple platforms.

Depending on the kind of video she’s making – whether it’s a recipe, a day-in-my life vlog, or a makeup tutorial – it may take anywhere from a few hours to a few days to fully produce. She has to shop, plan, set up her background and lighting, shoot and then edit.

AI creators can skip nearly all of those steps.

“It bears the question: Is this going to be something that we can out compete? Because I am a human. My output is limited,” Ms Sambasivam, based in North Carolina, said. “There are months where I will be down in the dumps, and I’ll post just the bare minimum. I can’t compete with robots.”

She started building her channel while living with her parents during the Covid pandemic. Without a set-up, she said she duct-taped her phone to the wall to film. Eventually, she spent money she made as an influencer buying tripods, lighting, makeup and food for her videos. It took years to build her following.

Ms Mckenzie said she considered being a more traditional influencer, but didn’t have the money, time or setup. That’s why she created Gigi.

“My desk at home has a lot of books and stuff,” she said. “It’s not the most visually appealing. It definitely makes it easier that you can just pick whatever background you want with AI.”

Kaaviya Sambasivam

Kaaviya Sambasivam“Real” life on AI videos

When Ms Mckenzie started, she turned to Google’s Veo 3 chatbot, asking it to generate a woman – someone to stand in as her.

Gigi is her age, 21, with tanned skin, green eyes, freckles, winged eyeliner and long black hair. She then asked the chatbot to make Gigi talk. Gigi now starts each video chiding commentators who accuse her of being AI. Then, mockingly proving them right, she eats a bedazzled avocado or a cookie made of slime.

Ms Duffy said digital alterations aren’t new. First, there were programs like Photoshop, used for image editing. Next, apps like FaceTune made it easier for users to change their faces for social media. But she said the main precursor to today’s hyper-realistic AI videos were celebrity deepfakes, emerging in the late 2010s.

But they now look much, much more real, Ms Duffy said, and they can spread faster.

AI videos run the gamut from the absurd – a cartoon of a cat working at McDonald’s – to the hyper-realistic, like fake doorbell camera footage. They represent every genre – horror, comedy, culinary. But none of it is real.

“It’s become, in some ways, a form of meme culture,” Ms Duffy said.

One 31-year-old American woman living in South Korea has a TikTok page dedicated to an AI-generated puppy, Gamja, who wears headphones, cooks and curls his hair. She’s received millions of views as well as partnerships from companies who want to be featured in her videos.

“I wanted to blend things that people love, which include food and puppies, in a way that hadn’t been done before,” she said.

One of the biggest AI content creators on TikTok is 27-year-old Daniel Riley. He has an audience of millions, but they have never seen his face. Rather, his “time travel” videos have earned him nearly 600,000 subscribers and tens of millions of views.

“POV: You wake up in Pompeii on eruption day” and “POV: You wake up as Queen Cleopatra” are some of his most popular titles, taking viewers through a 30-second-long fictionalised day in ancient history.

“I realised I could tell stories that would normally cost millions to produce and give people a look into different eras through their phone,” he said.

And he’s developed another stream of income – a bootcamp to teach others how to make similar AI videos for a monthly fee.

Will anyone know the difference?

“Stop calling me AI,” Gigi says at the beginning of each TikTok. She’s arguing with sceptics’ – but some audience members unquestioningly believe she’s real.

On one hand, AI videos that are almost indistinguishable from reality pose a real problem, Ms Lingel said, especially for young kids who don’t yet have media literacy.

“I think it’ll be almost impossible for an ordinary human to tell the difference soon,” she said. “You’re going to see a rise in misinformation, you’re going to see a rise in scams, you’re going to see a rise in content that’s just…crappy.”

On the other, AI videos can be mesmerising, experts said, offering cartoonish, exaggerated material.

“It’s those images and posts that seem to toe the line between reality and duplicity that capture our attention and encourage us to share,” Ms Duffy said.

A Harvard University study indicated that among AI users between the ages of 14-22, many say they use it to generate things like images and music.

Still, she said, the question is if human discernment can keep up with rapidly improving technology.

Almost every day, the creator of Gamja said she hears from people online, worried about her AI-generated puppy: They think he’s eating foods that are unhealthy, they say – because they think they’re watching a real dog.

Source link