The study’s research team is part of a research centre (Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Health and Social Care) partnering with local health districts and other key stakeholders. This allowed first in contact with health and social care programs throughout research and services’ network. A snowballing method was used to branch further out into other health and social care programs and community leaders and volunteers through common and known participants.

Recruitment and participants

The study was advertised in the health and social care service networks, by sending an expression of interest email (EOI) to several health and social agencies that provide health and social services in the Sydney Metropolitan area. Program representatives were volunteers who contacted the principal investigator (MGU) for enrolment and other information. Programs representatives were eligible to participate if they were assisting (formally or informally) priority populations, including culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, or programs that have a role (funding, liaison, advocacy) assisting health and social care programs (e.g., Ministry of Health).

Participants were involved in the implementation of health and social care programs in the Sydney Metropolitan area either as administrators, service providers or volunteers and/or community leaders. Health and social care programs were defined broadly and not identified a priori.

Data collection and measures

Semi-structured interviews exploring innovative policy supports were conducted online by the first author (MGUG) and lasted approximately 45 minutes each.

This analysis is part of a broader study aimed at mapping integrated health and social care innovations with a CALD focus across Greater Sydney using Wodchis and Collaborators5 Framework (See full details Table 1). Interviews were conducted from June 2023 to April 2024. Interpreters were not required as all participants were proficient in English.

Analysis

Demographic descriptive analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Version 29. The thematic analysis and coding involved and consultation a team of authors, who were experts in qualitative technique (several meetings were held to endorse themes and structure of this work).

Using the interview, it was determined the CALD intake of each program, categorised them as follows:

-

1.

CALD-specific: programs serving only CALD clients (100%)

-

2.

High intake: programs serving 50% or above CALD clients (open to mainstream Australians)

-

3.

Moderated uptake: programs serving below 50% CALD clients (open to mainstream Australians)

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee (RPAH Zone) of the Sydney Local Health District (protocol number X22-0406) and the South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2023/STE00775). All participants provided written informed consent. All participants included in this study provided written informed consent.

Sample

Twenty-seven participants from social (n = 10) and health care (n = 14) organisations based in Metropolitan Sydney were part of the study sample. A total of 27 interviews were conducted. Of the sample, 71 percent were female, the mean age of participants was 50.18 (SD = 12.36). Fifty-six percent of participants had 16 and above years of experience in their sector, 40 percent had a bachelor’s degree, and 36 percent had a postgraduate degree. Forty percent of participants were service managers, and 17 percent were staff specialists. Seventy-nine percent of participants selected English as their preferred language.

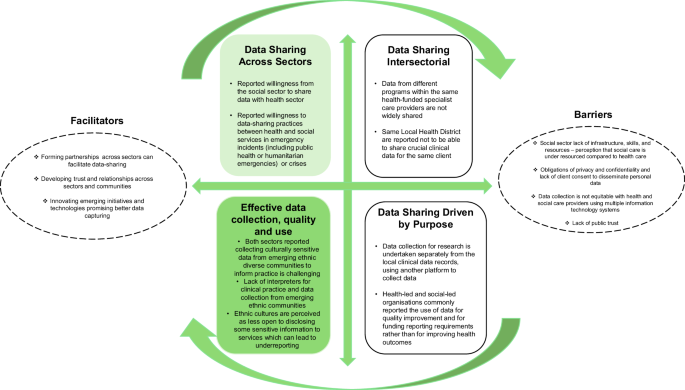

The analysis identified several themes relevant to the ‘Innovative Policy Supports For Integrated Health And Social Care Programs Framework’ devised by Wodchis et al.5. These are presented under the framework domains outlined below. Additional themes including facilitators, barriers to data-sharing and quality of data categories reported by participants are also mapped. Figure. 1 presents an overview of the themes explored.

Insights, facilitators and barriers for data sharing in health and social care.

Data sharing across health and social sectors

Generally, there was a reported willingness from the social sector to share data and it was reported that interagency individual data can be shared across services on a need basis. Participants from social care services perceived that health systems are unwilling to share individual data. Participants reported more willingness to data-sharing practices between health and social services in emergency incidents (including public health emergencies) or crises. These include domestic and legal incidents, as well as humanitarian intake to Australia.

Interview #024 participant reported ‘Humanitarian arrivals are coordinated. We had disability support, and it’s sharing with us one of her case studies where, because we’re going to know so we get information beforehand from Home Affairs from Settlement Service International, because there’s going to be this person with an extreme disability or health condition. The nurse had to then liaise, say, with Liverpool hospital the client is going to land a Sydney Airport at this time. We need to make sure that you have a bed available, because we don’t want them sitting in emergency department’.

During the pandemic crisis, there was an open case to expedite essential communication of population data. Interview #027 participant reported ‘When we saw the Delta, these were going not well, what we had meetings with the Department of Customer Service would have community sentiment surveys, checking data, and Transport for New South Wales would have community mobility data, who was moving where and how. And I would have the data from overnight where our cases were, if we were seeing particular patterns, in the cases emerging’.

Data-sharing within one sector

Data from different programs within the same health-funded specialist care providers are not widely shared. It is commonly reported that multiple recording systems are used in the same organisation. Interview #008 participant reported ‘I created another database to help us fill in those databases. They’re all different. And not everybody is funded by the same organisation. So same funders, but everyone has different commitments. The Department and Community and Justice bought this sort of key performance indicators in combination with New South Wales Health’.

Similarly, services within the same Local Health District are reported not to be able to share crucial individual data for the same client, given the lack of incompatibility between two different systems for data recording (e.g., Electronical Medical Records vs Titanium software).

Data-sharing for external research and evaluation

Pilot evaluation projects are undertaken predominately by university and health systems in partnership. Data collection for research is undertaken separately from the local individual data records, using another platform to collect data. Ethical consent must be obtained when reporting clinical data. Electronic medical records are not generally used for research.

Data-sharing for technical reports for service improvement

Health-led and social-led organisations commonly reported the use of population data for quality improvement and for funding reporting requirements. General de-identified service data is shared and used via service providers’ websites or other form of reporting. Data from different service providers (e.g., GPs, primary care, and NGO service providers) are used to detail service episodes and usage with minimal data.

Effective data collection, quality and use

Both social- and health-led organisations reported collecting culturally sensitive data from emerging ethnic diverse communities to inform practice is challenging. One of the main reasons is the lack of interpreters who can assist in clinical practice and data collection from emerging ethnic communities. In addition, different ethnic cultures are perceived as less open to disclosing some sensitive information to services which can lead to underreporting.

Participants report a lack of comprehensive longitudinal individual data being shared across the health system (primary and secondary). There is also the perception that there is a better quality of data for research purposes compared to the clinical data recorded routinely.

Barriers to data-sharing

The main barriers to data sharing across sectors cited by participants are obligations of privacy and confidentiality and lack of client consent to disseminate individual data.

Interview # 016 participant reported ‘I think that’s because of the data security and the data sharing policies of New South Wales Health and the various social service agencies that we’re talking about. it’s sensitive health or social information. You can’t share that. But I think, a potential way around that is if these services are integrated’.

Lack of infrastructure, skills, and resources (e.g., IT support or de-identification processes) particularly in the social care sector is frequently reported. Interview #026 participant reported ‘We don’t have a strategy for it. So we don’t know why we really want to collect this data. So there’s no real purpose. Apart from reporting. we don’t have the IT systems that are really smart enough to support reasonably’.

There is a lack of interoperability within and across both health and social systems. It has been reported that data collection is not equitable with health and social care providers using multiple information technology systems. Interview # 025 participant reported ‘So each branch of the of the organisation now has a different formula and criteria for recording their data’.

Trust in social and health sectors when handling individual data is also a significant barrier, particularly with government-led existing systems including ‘My Health Record’. Interview #019 participant reported ‘Data sharing is that it raises really big issues around how much the government knows, and how much the government should know’.

Facilitators for data-sharing

Systems have developed emerging ways to share their existing individual data. Both health- and social-led services reported setting up interagency meetings with several stakeholders for emergency incidents as a way of communicating and sharing individual sensitive data. Organisational flexibility is also reported. Services are still using and accepting using fax, phone and email to communicate (e.g., social providers and GPs). Interview #002 participant reported ‘We’ve got referral forms, hospitals, we’re still phoning hospitals a bit old school, you still need to ring and talk to the social workers. Some general practitioners still have fax machines.

Services and practitioners (e.g., legal aid services) are also willing to push some individual data-sharing boundaries depending on what jurisdiction they are in as each jurisdiction has legislated and varying rules around information sharing.

Forming partnerships across sectors can facilitate individual data-sharing and using basic global platforms are reported as a facilitator, especially the use of Microsoft Excel spreadsheets for data collection and reporting in both health and social-led organisations. Participants highlighted that using existing pathways for data collection and recording may be beneficial. ‘My Health Record’ was originally created to remediate individual clinical data collection and reporting; however, this platform has not succeeded, mainly due to the lack of public trust even across health-led systems of primary and secondary care which is in line with global evidence.

Innovative ways of capturing data have also emerged from interviews. These included the development of the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL), and Integrated Care Progress and Outcomes dashboard which currently captures real-time clinical data which are both governed by the health sector.

Reflections

This study sought to expand understanding about the uptake of data-sharing practices (changes or innovating policies) across health and social care systems and the barriers and facilitators of data integration of services in the most populous city in Australia, Sydney Metropolitan. Specifically, existing system-level data-sharing practices across sectors and within sectors, as well as research driven and funding driven data-sharing patters and quality of data in a priority population context, were analysed and mapped.

While our local systems collect a large volume of service data from public social and health services, data rarely reaches the desks of clinicians and service managers. Our study highlights the heterogeneity of the data collected, with a lack of unified information technology platform that allows for data-sharing across health and social care systems. In line with existing evidence25, minimum data standards for sharing information in a systematic way while allowing innovation are not incentivised and supported at local level.

While there are some innovations in capturing social population-base data16, our study demonstrates there is a lack of infrastructure, strategy, skills, and resources to collect and share data effectively in the social care sector. There is a perception from social care providers that the data they collect is mainly for reporting to funders with no real strategy behind it. This may be also associated with a lack of more comprehensive understanding and measurement of adult social care needs at a clinical and social level, and how they are assessed and coded within variables in big databases26.

Health data recording initiatives are proliferating with different degrees of success19,27,28,29. Some progress has been established to create more interoperable data systems. The introduction of ‘My Health Record’, for example, tracks client health service usage, but has experienced the lack of trust from the Australian public27 regarding how government agencies collect, share, protect or exploit their personal data28,30,31.

This demonstrates that barriers to data sharing remain even at same sector level (e.g., primary to secondary health care) and are even more underdeveloped in cross-sectoral settings (e.g., social system to health system). While our study uncovered conditions that were conducive to data sharing under special circumstances pandemic, domestic violence incidents, and for humanitarian entrants, our real-time day-to-day integrated social and health data-sharing practices are limited. The key component is the understanding that data-sharing will involve a transformation of systems, consisting of structures and processes, and that may include at times conflicting agendas32. Policy-makers, planners, and implementers need to work toward achieving and continuously maintaining stakeholder alignment; only in this context can successful technological solutions be developed33.

A single architecture is unlikely to fulfill all requirements simultaneously i.e., be real-time, dynamic, event-level data centred on the client and development of stable, curated repositories of longitudinal health/social records for integrated care, research and planning. Hence, there is now a need to identify potential architectural components and designs and map their benefits, costs and trade-offs32. From the policy lens, strengthening and harmonising the legal and policy frameworks that facilitate the integration of health and social care data is fundamental. It has been postulated that building a social license to ensuring that data integration operates as a public good18,34 could be the way forward. By leveraging data and technology, sector partners have an opportunity to improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability of efforts that address health and social needs as a regular component of service delivery35.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. While we aimed to conduct a throughout mapping study that encompasses all the services in Sydney Metropolitan, we acknowledge not all services working with priority populations participated given the voluntary nature of the study.

The strengths of this study include capturing the voices of key stakeholders, namely priority community representatives (leaders and volunteers), health and social care decision makers and staff regarding the state and depth of social and health care integration, including data-sharing practices and its local knowledge and evidence that is lacking from the literature.

A shift of organisational culture and a suitable model of data of monetisation that incentivises data-sharing could be fundamental for changing future data-sharing practices25,36. Specifically, addressing and recognising the inherent tension from the key health and social care stakeholders are a way forward. It has been postulated employing techniques to facilitate data integration such as involving stakeholders at an appropriate time and inviting external stakeholders and routinising site visits with those stakeholders involved in the integration37.

In Australia, the key cultural elements that need to be addressed are cross-sectorial readiness, misinformation about data sharing and the lack of understanding of current legal requirements by health and social care professionals. A way of moving forward includes a revision of current data-sharing policies in health and social care, and analysing the existing gaps and misalignments to tailor a framework for better serve priority populations.

As a first step, a future line of research should focus on mapping the misinformation landscape locally, identifying common myths or misunderstandings among health and social care professionals as well as assessing legal literacy amongst both sectors, and its impact on data-sharing behaviours.

Source link