Did Life Begin in the Cold? New Experiments Point to an Icy Origin

Experiments reveal that unsaturated lipid membranes promote vesicle fusion and DNA retention during freeze–thaw cycles, highlighting icy environments as potential drivers of protocell evolution.

Today’s cells are extraordinarily intricate. They contain internal scaffolding known as cytoskeletons, carefully controlled chemical reactions inside and outside the cell, and genetic material that governs nearly all aspects of their behavior.

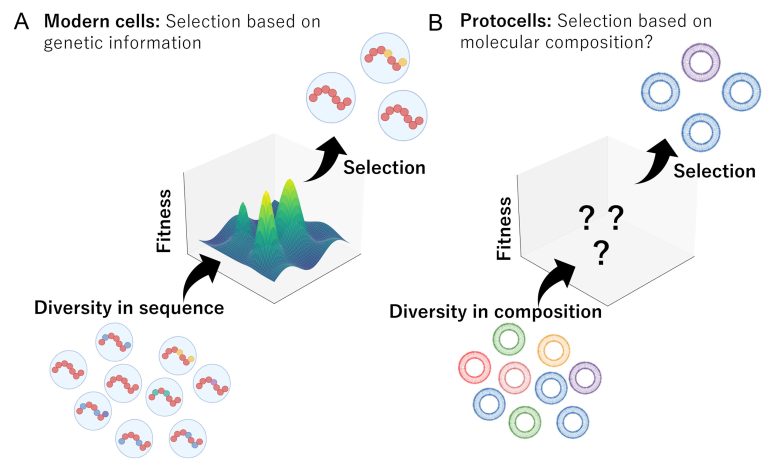

This complexity allows cells to adapt to many environments and compete successfully based on their fitness. By contrast, the earliest cell-like structures were likely far simpler, consisting of small lipid bubbles that trapped basic organic molecules. Understanding how such primitive compartments transitioned into fully developed modern cells remains one of the central challenges in origin-of-life research.

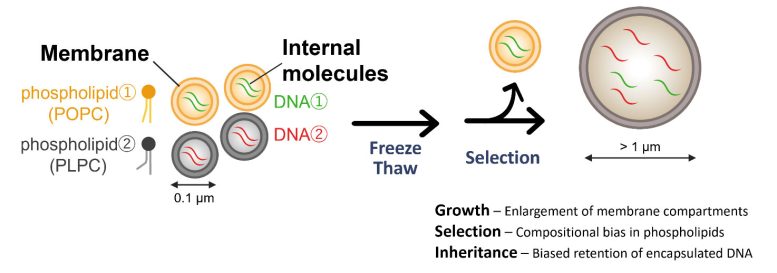

In a new study, researchers, including scientists at the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at the Institute of Science Tokyo, investigated how simple protocell models respond to realistic, non-equilibrium conditions thought to resemble those on early Earth. Rather than promoting a single theory about how life began, the team focused on testing how variations in membrane chemistry affect protocell growth, fusion, and the ability to retain biomolecules during freeze–thaw cycles.

Lipid Composition Shapes Protocell Membrane Properties

To investigate this, the scientists studied how the makeup of a membrane affects the growth and behavior of protocells. They created tiny, bubble-like spheres called large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) using three types of phospholipids: POPC, PLPC, and DOPC—molecules similar to those found in modern cell membranes.

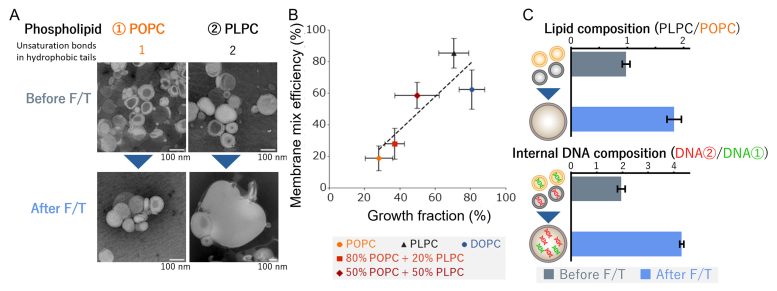

“We used phosphatidylcholine (PC) as membrane components, owing to their chemical structural continuity with modern cells, potential availability under prebiotic conditions, and retaining ability of essential contents,” said Tatsuya Shinoda, a doctoral student at ELSI and lead author. Although these molecules are closely related, their structures differ in important ways. POPC contains one unsaturated acyl chain with a single double bond. PLPC also has one unsaturated acyl chain, but it includes two double bonds. DOPC features two unsaturated acyl chains, each with one double bond. These subtle differences affect membrane behavior. POPC tends to produce relatively rigid membranes, while PLPC and DOPC create membranes that are more fluid.

The team then exposed the LUVs to repeated freeze/thaw cycles (F/T) to mimic temperature fluctuations that early protocells may have experienced. After three F/T cycles, vesicles rich in POPC clustered together in tightly packed groups. In contrast, vesicles containing PLPC or DOPC fused into much larger compartments. The likelihood of fusion and growth increased as the proportion of PLPC rose. Overall, lipids with more unsaturated bonds were more prone to fusion and expansion.

“Under the stresses of ice crystal formation, membranes can become destabilized or fragmented, requiring structural reorganization upon thawing. The loosely packed lateral organization due to the higher degree of unsaturation may expose more hydrophobic regions during membrane reconstruction, facilitating interactions with adjacent vesicles and making fusion energetically favorable,” remarked Natsumi Noda, researcher at ELSI.

DNA Retention and Molecular Mixing in Icy Environments

These results have important implications for early evolution. When vesicles fuse, the molecules trapped inside them can mix and potentially react. In the chemically rich environment of early Earth, such merging events may have brought together key ingredients needed for increasingly life-like systems.

To test this idea, the researchers compared how effectively 100% POPC and 100% PLPC vesicles retained DNA. PLPC vesicles not only captured more DNA before F/T treatment, but they also held on to more DNA than POPC vesicles after each freeze–thaw cycle.

Most origin-of-life scenarios focus on environments such as drying and rewetting surfaces on land or hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. This study suggests that icy regions could also have been significant. On the early Earth, freeze/thaw cycles likely occurred repeatedly over long timescales.

As ice formed, it would have pushed dissolved substances out of growing crystals, concentrating organic molecules and vesicles in the remaining liquid. Membranes composed of more unsaturated phospholipids are loosely packed, which encourages vesicle fusion and mixing of contents. At the same time, highly fluid membranes can be vulnerable under freeze–thaw–induced stress, increasing the risk that internal contents will leak out.

This creates a trade-off between permeability and stability. The membrane composition that performs best would depend on the surrounding conditions.

“A recursive selection of F/T-induced grown vesicles across successive generations may be realized by integrating fission mechanisms such as osmotic pressure or mechanical shear. With increasing molecular complexity, the intravesicular system, i.e., gene-encoded function, ultimately may take over the protocellular fitness, consequently leading to the emergence of a primordial cell capable of Darwinian evolution,” concludes Tomoaki Matsuura, professor at ELSI and principal investigator behind this study.

Reference: “Compositional selection of phospholipid compartments in icy environments drives the enrichment of encapsulated genetic information” by Tatsuya Shinoda, Natsumi Noda, Takayoshi Watanabe, Kazumu Kaneko, Yasuhito Sekine and Tomoaki Matsuura, 31 October 2025, Chemical Science.

DOI: 10.1039/D5SC04710B

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

Source link