Photo: Courtesy of Any Lucía López Belloza

Any Lucía López Belloza was trying to board a flight from Boston to Austin when immigration enforcement agents arrested her on November 20. The Babson College freshman had planned to surprise her family for Thanksgiving. But within 48 hours, López Belloza was instead deported to Honduras, a country she left as a 7-year-old child when her family came to the U.S. to seek asylum.

López Belloza was expelled despite a court order blocking the government from doing so while her immigration case is pending. Trump administration officials have called her a “criminal,” and the Department of Homeland Security claims López Belloza entered the country without authorization in 2014 and that an immigration judge ordered her removal in 2015. “She received full due process and was removed to Honduras,” DHS spokeswoman Tricia McLaughlin said in a statement. López Belloza’s attorney, Todd Pomerleau, disputes this account, saying that government records indicate his client’s case was closed in 2017.

Speaking from her grandparents’ home in northern Honduras, López Belloza says, “The president likes to say that we’re all criminals. We’re not.” Below, she shares what it was like to be shuttled between immigration detention centers and suddenly deported, how she’s adjusting to life in Honduras, and what comes next.

I didn’t sleep the night before my flight; I was so excited. I was happy to surprise my family and see their faces. My flight was at five in the morning. When I got to the airport, everything was fine. I passed through TSA and got a coffee. When it was time to board, the agent scanned the ticket on my phone, and something appeared on the computer, like an X. After two attempts, they said, “Go to customer service. There’s something wrong with your ticket.” There were two ICE agents waiting for me at the desk, one man and one woman. They were dressed normally and did not identify themselves. They were like, “You’re going to come with us because you need to fill out a bunch of paperwork.”

I was like, “Paperwork? Is there something wrong with my luggage? I actually have to hop on the plane. I have to leave right now.” They were like, “You’re not even gonna get on the plane.” That’s when I thought, This is ICE. I have seen a bunch of videos on how they’re treating people. If I resist, it’s going to go worse for me, so I’m going to follow what they say. We exited the airport to the parking lot. They asked me to put my things in the back of a normal car, handcuffed me, and took me to the detention center. I was crying on my way there, telling them, “I’m a college student. I’m going home to surprise my parents. Do you guys not have a family?”

Once we arrived at the detention center, they made me wait a couple hours before they told me I had a deportation order that I didn’t know about. I immediately started having an anxiety attack. I couldn’t breathe; I was about to pass out. The agents were not helping me at all. I asked, “When will I get deported?” At the same time I was trying to process that, I was also worried about not turning in an assignment. I was so excited to go see my family that I didn’t care about it, but now I was blaming myself ’cause I procrastinated.

The detention center in Boston felt clean. We were given bananas and apples. If we had questions, the agents would open the door to the cell and tell us what was happening. If we wanted to talk on the phone, they would give us a time. But around seven in the morning on Friday, they called those of us who were going to be transferred. I had a small carry-on and a backpack, so I asked to check that my items were there, like my phone — I’m a teenager who cannot live without a phone. Then they put handcuffs on us, a chain over our waist and our feet, like criminals.

They transported us in the kind of van that you put dogs in. We were all sitting in a row facing a white wall. It was not a very big space. We were there for more than two hours. Eventually, we were taken to an Air Force base, where there were more vans. We boarded the plane and it was full. There were more than 120 people. They told us that they’d give us two bathroom passes and lunch. I thought, At least when I go to the restroom, I’ll be able to wash my face. Hopefully there’s a mirror. I’ll probably wash my mouth, too. But no. When I went to the restroom, they left a handcuff on one hand. There was no running water, just hand sanitizer. A lady in her 70s kept throwing up. She got no medical assistance and they kept the handcuffs on her. They were like, “Just drink water. There’s a bag.”

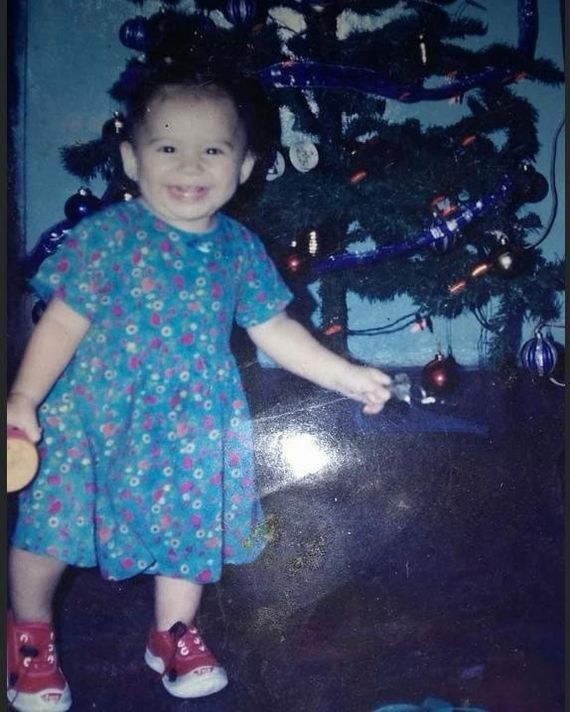

López Belloza as a child in Honduras.

Photo: Courtesy of Any Lucia López Belloza

We landed after about four hours. They had told us we were going to Louisiana, but we realized we were actually in Texas. When we got to the Port Isabel Processing Center, we were brought to a men’s cell where there were four other women already. We asked the agents, “Can we have a toothbrush? Food? We haven’t eaten, it’s dinnertime. Can we have blankets? Can we make a phone call?” Some of the ladies were asking for clothes. They brought us toothbrushes, toothpaste, and deodorant, that’s all.

We didn’t get a phone call. I was worried because I was able to call my parents twice on Thursday, but at this point, it was Friday night and they didn’t know any updates from me. We were still asking the agents for blankets; thank God that the ladies who were already there had some and shared. They also had some food, so we were able to eat a little. The agents had given us dirty water that tasted really nasty, like Clorox. I also hadn’t showered in two days. I felt dirty.

Four or five other women were brought to the cell after we arrived. We couldn’t really sleep because of those interruptions. At that point, it was Saturday morning, and I hadn’t slept for three days. Around 3 a.m., agents called my name and somebody else’s, handcuffed us again, and took us to the bus. It was just me and another woman from the cell; the rest of the people on the bus were all men. When they asked where we were from and we said Honduras, they were like, “That means we are all gonna get deported.” We were in a bad place, but we were also trying to make it fun, so we began joking about it. “We haven’t been there a long time. We’re about to eat some real food.”

At one point, an agent said some people were going to be sent to San Diego. We were all shocked, like, “We don’t want this to happen to us anymore. We prefer to go back to our country.” That’s because detention feels like torture, and for me, it was only three days. Many women in those cells had been in the system for months, even a year. After a few hours of waiting, it really hit me that I was getting deported. I freaked out, thinking, Why is everything happening so fast? I got to tell my family that I’m in Texas, but now I’m leaving for Honduras. Not even within 24 hours, I’m being transferred. This is not right.

When we finally got on the plane more than three hours later, it was all Hondurans. I think I was the youngest person, but there were people of all ages from their 20s to their 60s. We were given a sandwich, some carrots that didn’t even taste like carrots, and water. They took our handcuffs off halfway through the flight. We landed in Honduras around noon local time. We got our things and got on another bus to take us to a little house where they gave us food and our phones.

A woman shared internet with me so I could call my mom. I was like, “Mom, can you hear me? I got deported.” She said, “It’s okay. Your aunt and your grandma are waiting for you there.” And I was like, “How did you guys find out?” She said, “We haven’t slept. We’ve been trying to look for you and we barely found you.” I was like, “I’m sorry that I failed you,” and I told her, “I hope I see you soon. Send my sisters over ’cause I miss them.”

The process after arriving was fast. We were given our birth certificate, because they took my ID. I plan to continue going to college over here, so I need to get a driver’s license and a passport. That is something that I’m struggling with because I’m considered a minor in Honduras. I can’t get my passport because both of my parents are not here.

López Belloza with her family in Texas, whose faces are blurred to protect their privacy.

Photo: Courtesy of Any Lucía López Belloza

I didn’t find out that a judge ordered the government not to deport me until I got to talk to my lawyer after I arrived here. One of the ladies that I was with was supposed to go free on bond; she paid it and still got deported. Trump is just trying to get rid of innocent people. Me, a girl who’s in college, you can see that I’m no criminal.

The faculty and staff at Babson understand my situation and have been so helpful. I’m going to finish my semester online. Hopefully, I can continue college here, and if I go back, Babson can take some credits. I am trying to make a bad situation positive. The only thing that I want for the future is to continue college and, from there, open up a business for me and my parents.

It’s been nearly two weeks, and I’m getting used to everything. It just feels like I don’t belong here. My family in Honduras has been so helpful and I haven’t really had alone time, which I’m glad for, because I feel like if I do, I’ll fall into a dark hole. Everything right now is so hard. I’m not with my mom, I’m not with my sisters.

My parents are sending me money because everything in Honduras is expensive. I think they’re struggling, specifically my mom. She is my best friend. I failed her by not telling her that I was coming to surprise them. We always pray and put ourselves into God’s hands when we go anywhere. My 5-year-old sister still believes that I might go home for Christmas. She said, “You’re just there right now helping our grandma.” But it’s the opposite: She’s helping me.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Source link