Scientists Discover Strange New Parasitic Wasp Species in the U.S.

The lab is contributing to a broader initiative aimed at studying the diversity of oak gall wasps and their parasites.

Researchers, including faculty from Binghamton University, State University of New York, have discovered two parasitic wasp species in the United States that were previously unknown to science.

While oak gall wasps and the creatures that prey on them may lack the beauty of butterflies, they are increasingly drawing the attention of both scientists and nature enthusiasts.

These insects, measuring just 1 to 8 millimeters in length, create the tumor-like plant growths known as “galls.” Small as a pinhead or large as an apple, galls can take striking shapes, with some resembling sea urchins or saucers, explained Binghamton University Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Kirsten Prior, who also co-leads Binghamton’s Natural Global Environmental Change Center.

If these wasps symbolize anything, it is the richness of biodiversity. North America is home to roughly 90 species of oak trees, which in turn host about 800 species of oak gall wasps. Parasitic wasps exploit these galls by laying their eggs inside, eventually consuming the oak gall wasp within.

But how many species of parasitoid wasps are out there? That’s a question that scientists — both academic researchers traveling the globe and everyday citizens in their own backyard — are working to answer.

A recent article published in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research gives insight into a previously unknown level of species diversity. In addition to Prior, co-authors include current graduate student Kathy Fridrich and former graduate student Dylan G. Jones, as well as Guerin Brown, Corey Lewis, Christian Weinrich, MaKella Steffensen, and Andrew Forbes of the University of Iowa, and Elijah Goodwin of the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture in Tarrytown, N.Y.

This discovery is part of a larger research effort. In 2024, the National Science Foundation awarded a $305,209 grant to Binghamton University for research into the diversity of oak gall wasps and parasitoids throughout North America. The project is a collaboration between Prior, Forbes at the University of Iowa, Glen Hood at Wayne State University, and Adam Kranz, one of the creators behind the website Gallformers.org, which helps people learn about and identify galls on North American plants.

The NSF grant investigates a core question: How do gall-forming insects escape diverse and evolving clades of parasitic wasps — and how do parasites catch up? To answer that question, researchers are collecting oak gall wasps around North America and using genetic sequencing to determine which parasitic wasps emerge from the galls. Among them are Fridrich and fellow Binghamton graduate student Zachary Prete, who spent the summer on a gall- and parasitoid-collection trip from New York to Florida.

“We are interested in how oak gall characteristics act as defenses against parasites and affect the evolutionary trajectories of both oak gall wasps and the parasites they host. The scale of this study will make it the most extensive cophylogenetic study of its kind,” Prior said. “Only when we have a large, concerted effort to search for biodiversity can we uncover surprises — like new or introduced species.”

Discovering unknown species

Over the past several years, researchers with Prior’s lab traveled the West Coast from California to British Columbia, collecting approximately 25 oak gall wasp species and rearing tens of thousands of parasitic wasps, which were ultimately identified as more than 100 different species.

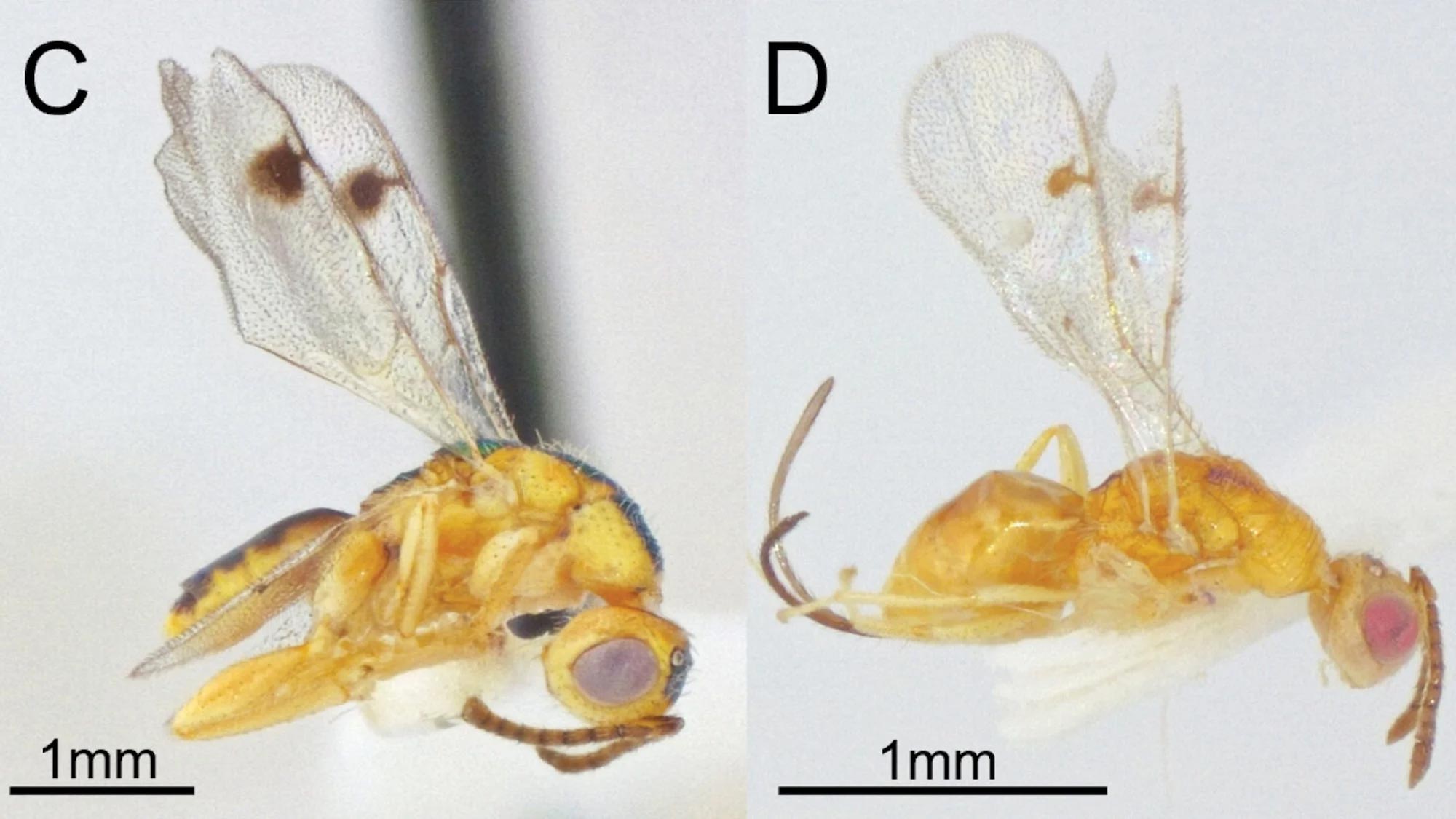

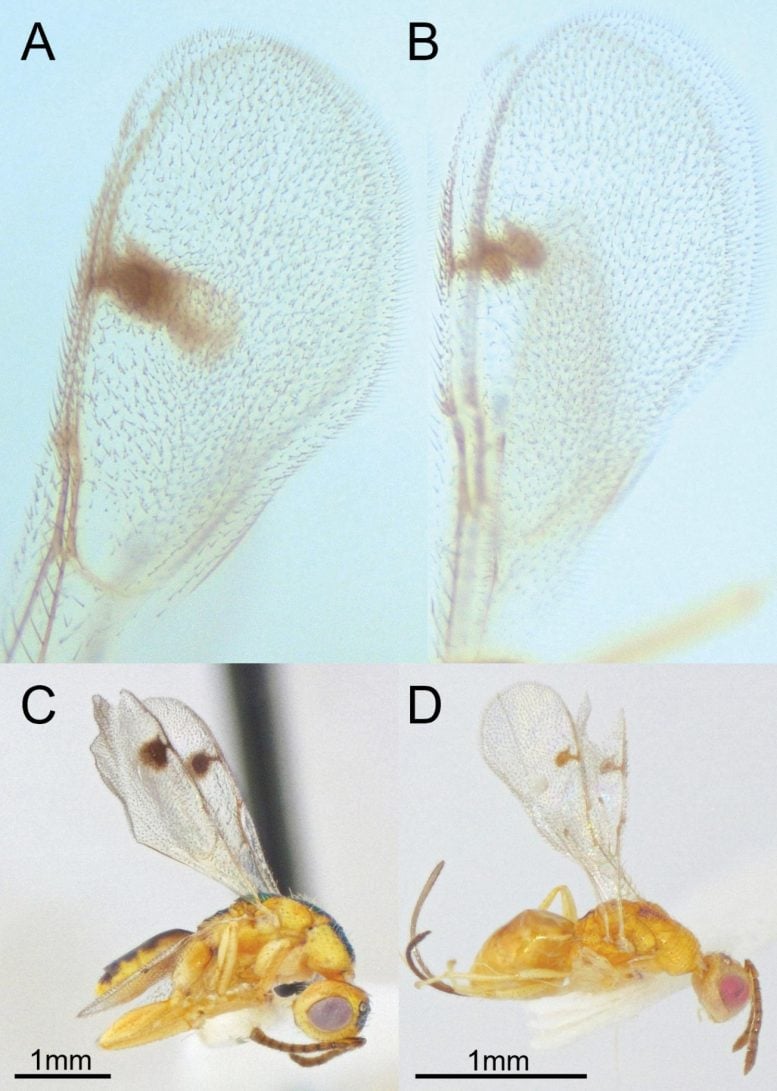

Some of the parasitoids, reared from oak gall wasp species from several locations, turned out to be the European species Bootanomyia dorsalis in the wasp family Megastigmidae. Researchers at the University of Iowa identified a similar wasp from collections they made in New York state.

“Finding this putative European species on the two coasts of North America inspired our group to confirm this parasitic species’ identity and whether it was, in fact, an introduced parasite from Europe,” Prior explained.

Parasitic wasps are small and challenging to identify based on features alone. Because of this, researchers use genetic tools to confirm a species’ identity, sequencing “the universal barcoding gene,” Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit I (mtCOI), and comparing their results to reference libraries. What they discovered is that the European species B. dorsalis came in two separate varieties, or clades: the New York samples were related to species in Portugal, Iran and Italy, while the Pacific coast wasps were related to those from Spain, Hungary, and Iran.

“The sequences from two clades were different enough from each other that they could be considered different species. This suggests that B. dorsalis was introduced at least twice, and that the New York and West Coast introductions were separate,” Prior said.

And while they were found in at least four different oak gall wasp species from Oregon to British Columbia, all the West Coast B. dorsalis wasps were genetically identical, which means that their introduction was small and localized. The East Coast wasps had slightly more genetic diversity, which could indicate that there was less of a population bottleneck, or that the species was introduced more than once.

How did the European species get here? One possibility is that non-native oak species were intentionally introduced to North America. English oak, or Quercus robur, was widely planted for wood since the 17th century, and is found in British Columbia as well as several northeastern states and provinces. Turkey oak, Q. cerris, is an ornamental tree now found along the East Coast — including a spot near where B. dorsalis was discovered in New York.

There are other possibilities. Adult parasitic wasps can live for 27 days, so they could have hitchhiked on a plane, Prior said.

Researchers don’t yet know if these introduced species pose a hazard to native North American species. Other introduced parasite species are known to impact populations of native insects, she acknowledged.

“We did find that they can parasitize multiple oak gall wasp species and that they can spread, given that we know that the population in the west likely spread across regions and host species from a localized small introduction,” Prior said. “They could be affecting populations of native oak gall wasp species or other native parasites of oak gall wasps.”

Naturalists and citizen scientists play an important role in biodiversity research, such as the project that led to the discovery of the two B. dorsalis clades. Gall Week, a project hosted on the platform iNaturalist, encourages citizen scientists to collect galls during two seasons, and specimens from the NSF-funded study will be posted on the naturalist site Gallformers.org. Binghamton University ecology classes have participated in Gall Week, and also logged galls during the University’s annual Ecoblitz biodiversity event.

Biodiversity is a key component to healthy and functioning ecosystems — and one that is increasingly under threat due to global change.

“Parasitic wasps are likely the most diverse group of animals on the planet and are extremely important in ecological systems, acting as biological control agents to keep insects in check, including those that are crop or forest pests,” Prior explained.

Reference: “Discovery of two Palearctic Bootanomyia Girault (Hymenoptera, Megastigmidae) parasitic wasp species introduced to North America” by Guerin E. Brown, Corey J. Lewis, Kathy Fridrich, Dylan G. Jones, Elijah A. Goodwin, Christian L. Weinrich, MaKella J. Steffensen, Kirsten M. Prior and Andrew A. Forbes, 2 July 2025, Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

DOI: 10.3897/jhr.98.152867

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Source link