Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Everett Collection, Paramount Pictures

It’s summer 1975, and voracious moviegoers are about to see something with real bite. Forgive the silly pun, but there was before and there was after Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. That was true both for Hollywood and for every nervous beachgoer of the next 50 years. The sunbathers of sleepy Amity Bay are helpless against the unexpected great white shark that hunts their coasts; Spielberg’s talent for suspense, effective horror shocks, and ingenious reinvention of the classic animal-attack movie remain as impressive as ever. It may be a half-century old, but Jaws has lost none of its potency.

But it wasn’t the only amazing thing to hit the box office that year. While Bruce the shark tore through limbs, there were also conspiracy thrillers, period dramas, counterculture satires, and deeply anti-authority crime flicks to rule the roost. Artists of the stature of Stanley Kubrick and Dario Argento, with their utterly unique worldview and dazzling visual bag of tricks, were producing film-as-art on a high level. Combining the heady years of the antiwar movement, the disillusionment of Watergate, the mores of thr sexual revolution, and the uncertainty of where the world was headed next, the films of 1975 were truly remarkable. You might even argue it was one of the all-time great years for motion-picture-making. Here are ten of the best.

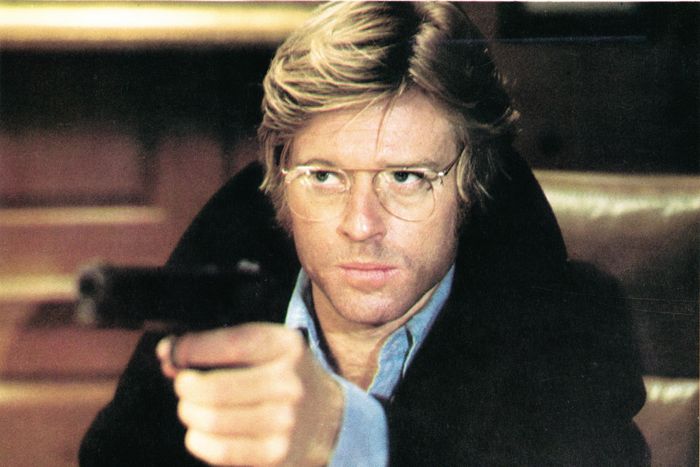

Photo: Paramount Pictures

In this pacy, slick Hollywood thriller that leans into the paranoia of Nixon-era wiretapping and mistrust of government institutions like the CIA, Robert Redford stars as a nerdy CIA researcher whose life changes in an instant when he goes out for lunch and returns to work to find that he is the sole surviving employee of his office; all his colleagues have been assassinated. Now on the run for mysterious reasons, he finds that his supposed handlers might have it out for him, too. Holing up in a random woman’s apartment for safety only complicates matters: the (un)lucky lady so happens to be Faye Dunaway, and naturally the pair of beauties fall for one another. With its doggedly cynical ending and complex network of conspiracy, this film is as 1975 as they come.

Photo: Warner Bros.

Borrowing from the likes of Luchino Visconti with his eye for exquisite period detail, the great Stanley Kubrick turned to 18th-century literary adaptation in his epic picaresque of a young cad named Barry Lyndon. With Ryan O’Neal as the conniving fool who social-climbs and lies his way through war and peace, Kubrick matches perfectly paced, often-hilarious satire with a sanguine view of human selfishness and impermanence. Taken from William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel, Kubrick manages to make a period piece truly unlike any other: a character study of a ridiculous man whom we nonetheless cannot keep our eyes off.

Photo: Howard Mahler Films

One of the major works of the Italian giallo genre — a hyperstylish series of sometimes-supernatural slasher flicks with great clothes and inventive deaths — Deep Red remains on top of the pile. In typical giallo fashion, its plot is complex, but Argento shows us his entire bag of cinema tricks here: intriguing, suspense-filled mystery, a fish-out-of-water character (David Hemmings) trapped in suspicion and witness to an appalling crime, some gorgeously perverse murders, and a synth-heavy Italo-disco soundtrack from prog rock band Goblin. It’s a classic for good reason.

Photo: Warner Bros.

Live-wire, frantic, and gruffly realistic, Dog Day Afternoon is one of the great crime films of all time and a quintessentially ’70s one, with its rough-hewn everyday characters and sweaty, imperfect flailing of a bank robbery. One of Al Pacino’s finest performances of the 1970s — which, with the Godfather films and Serpico, is an absurd hot hand — is as the enigmatic, wild-eyed Sonny, a man who performs a desperate bank robbery with his partner (the late John Cazale, by turns heartbreakingly clueless and dopily funny). With its buzzy energy and sympathetic — if bumbling — criminals, Lumet withholds crucial information from the viewer until the final portion of the film. We learn Sonny’s misdeeds are for an achingly vulnerable and unexpected reason: gender reassignment surgery for his partner.

Photo: Paramount Pictures

In Altman’s masterful, sprawling, epic ensemble piece capturing the revival of the country-and-folk scene in Nashville, a unique, freewheeling, almost pseudo-documentary style is used to explore more than a dozen characters in the glitzy music scene, from wannabes and hippies to conservative cowboys played by the likes of Shelley Duvall, Keith Carradine, and Karen Black. Part musical and part gleeful, prodding satire of the relationship of politics, showbiz, and spectacle, Nashville not only captures its own era’s spirit in allegory but maps uncomfortably well onto our own: American political life has hardly become any less superficial or corrupt in the intervening half-century.

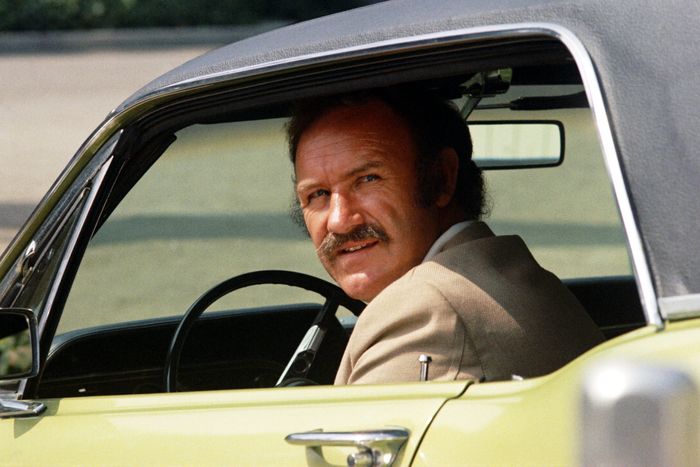

If there was one thing about 1975 on film — in fact, about ’70s films in general — that distinguished them, it has got to be the great, sometimes fatalistic, usually ambiguous endings. Turning away from the classical urge toward narrative resolution and tied-up loose ends, filmmakers like Penn — who helped usher in the New Hollywood with Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 — chose to leave their stories open-ended, despairing, even confusing. In Night Moves, Gene Hackman’s frustrated former athlete turned PI goes down to the Florida Keys to investigate the disappearance of a teenage girl. What he finds, instead, are more questions than answers. Refusing to simply hand the viewer a conclusion, Penn leaves Hackman spinning his boat in the warm Gulf waters, an iconic visual metaphor for the confusion and frustration of his unanswerable riddle — and perhaps of his entire era.

Photo: United Artists

No talk of movie culture in 1975 is complete without mention of the great Oscar winner of that year: Foreman’s adaptation of Ken Kesey’s novel swept the “Big Five” categories and proved to be a crowning achievement for Jack Nicholson in what many see as his signature role. In the tradition of so many of the great anti-authority films, Nicholson’s McMurphy is a man who has been wrongly institutionalized in a mental-health facility. The ensemble cast of oddballs he befriends are moved to action and solidarity by his heroic, small acts of rebellion. Pitted against the unforgettably evil Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), a sadist who drugs and abuses the unlucky patients in her care, McMurphy’s stand against the oppressive powers that be is tragic and poignant and spoke to the spirit of a time in which so many felt misunderstood.

Photo: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

After the breakout international success of Antonioni’s Swinging ’60s film Blow-Up (1966), the Italian master of moody alienation further explored the human condition outside of his native country. In his only outing starring Jack Nicholson, he shoots in far-flung locations from Chad to Germany and Spain following the travails of a guilt-haunted photojournalist caught up in a case of mistaken identity during a civil war. An enigmatic adventure film in the loosest sense, which often throws up more existential questions than it does concrete answers, The Passenger rewards a patient and curious viewer. Featuring one of the most breathtaking tracking shots ever committed to film — over six minutes in length, moving out of a hotel room and into a village square at 180 degrees — The Passenger is as cinematically lush as it is emotionally sparse.

Hal Ashby — the offbeat comic director of Harold & Maude and road movie classic The Last Detail — knew a thing or two about the so-called longhairs of the hippie era. (He was one.) So when he took on the chic environs of 1968 Beverly Hills, what better job to give his erstwhile, womanizing protagonist than a hairdresser? Ashby’s zany comedy of sexual manners and artificial Californian life was perfectly represented by legendary charmer Warren Beatty, opposite real-life flame Julie Christie. As a dimwitted product of a vapid culture, Beatty’s protagonist is hardly a figure to like — but Ashby’s amusing day-in-the-life exploration of his manic existence is wildly entertaining.

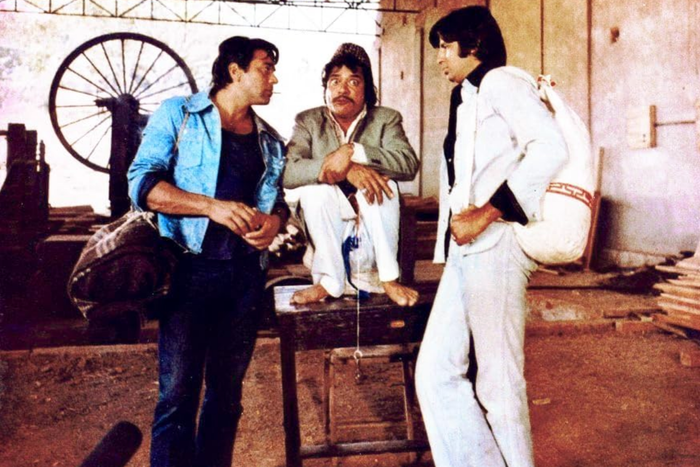

Photo: Dimension Pictures

Long before the incredible action-hybrid of Indian mega hit RRR, there was Sholay: an epic Hindi-language western adventure that captured the sweeping social change and economic tension of its time and place. Often considered one of the greatest Indian films ever made, with the scale of a Sergio Leone film and borrowed loosely from the plot of Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, it was made by director Ramesh Sippy over two harsh years in the mountains. Combining a western visual lexicon with deeply specific national themes, Sholay’s reputation has only grown over the intervening half-century since it was made.

Source link