The Fertility Problem Is Getting Worse with Time

As countries get wealthier, fertility drops. This relationship is nearly universal, and its implications are very dark. We all want people to live better lives, and it’s generally bad for societies to be at sub-replacement fertility. And although most people don’t think like this, I believe that lower birth rates are bad simply because we should want more people to exist. A country seeing its fertility fall from 4 to 3 to me is undesirable simply for the reason that more people is good, even if a TFR of 3 is still fine from an economic or social perspective.

The world is getting wealthier, so if we want to solve the fertility issue, that is arguably the main headwind we are facing. But the situation is even more troubling than that, as it seems that pro-natalists are battling against time itself. Even holding GDP constant, birth rates are collapsing over time.

To see how this has worked, we can look at the numbers from Our World in Data, which provides a spreadsheet of GDP and fertility rates for countries going back to the 1950s. As a starting point, check out the straightforward relationship between the two variables in today’s world. In this article, all GDP numbers are adjusted for inflation and the cost of living.

You can see that wealth isn’t the entire story when looking at how many poor modern countries there are with low fertility. This seems to have been a lot less common in previous decades. On the chart above, Ukraine is only at $16K a year, with a TFR of 0.98. Nepal had a GDP per capita of $5K, and was already below replacement. Even a passing familiarity with the data indicates that this didn’t happen in the 1980s and 1990s, or at least happened less often.

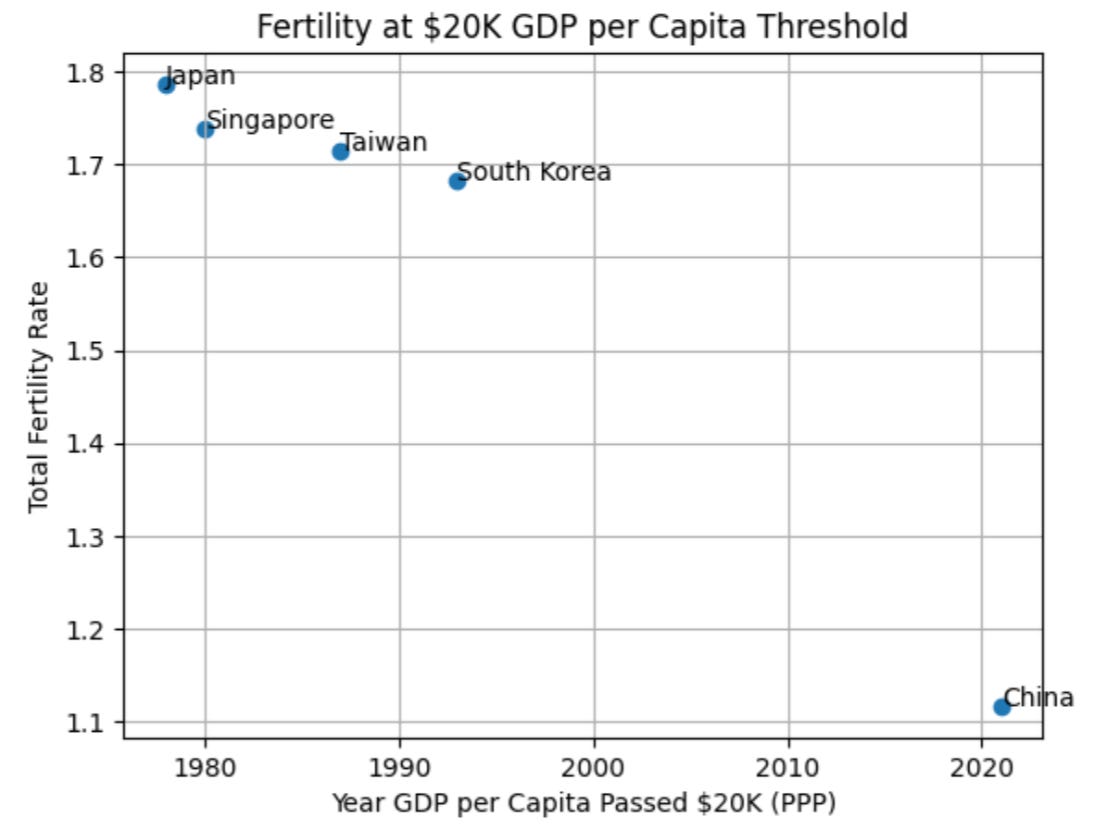

We can see a particularly extreme case of this in East Asia. China passed the GDP per capita threshold of $20,000 in 2021. That year, its fertility rate was 1.12. When Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan passed the same threshold, they were in much better shape, as can be seen in the chart below. The later an East Asian country achieved $20K, the lower its fertility at that moment.

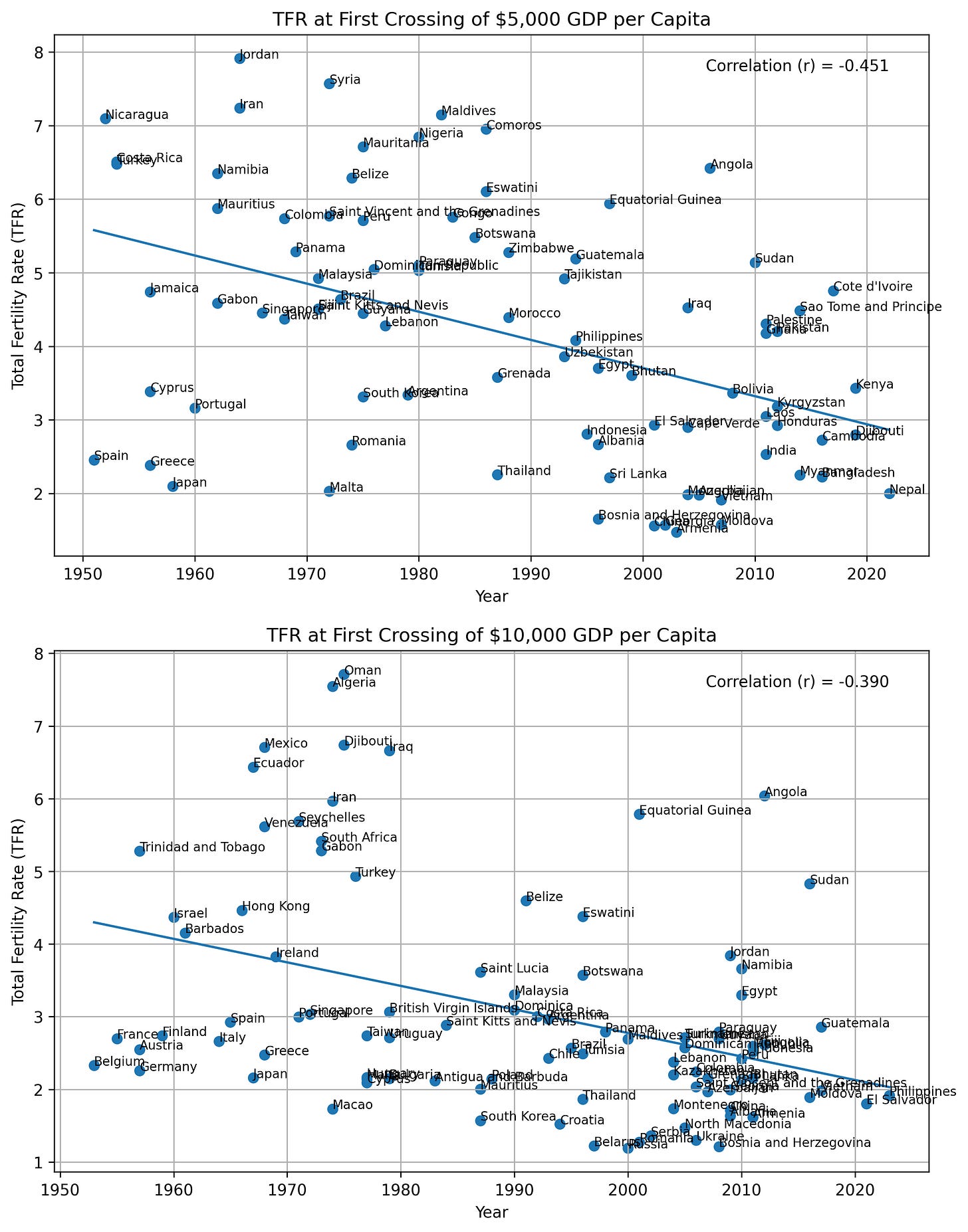

East Asian states other than China reached $20K a year between the late 1970s and early 1990s, and had TFRs in the range of 1.7-1.8 when they did so. Of course, China for decades had a one-child policy, so we must factor that into the analysis. But the pattern holds elsewhere. In the two charts below, I show the fertility rate in each country the year it first passed either $5K or $10K in terms of GDP per capita, in the cases where a nation has met either of those thresholds and the data is available.

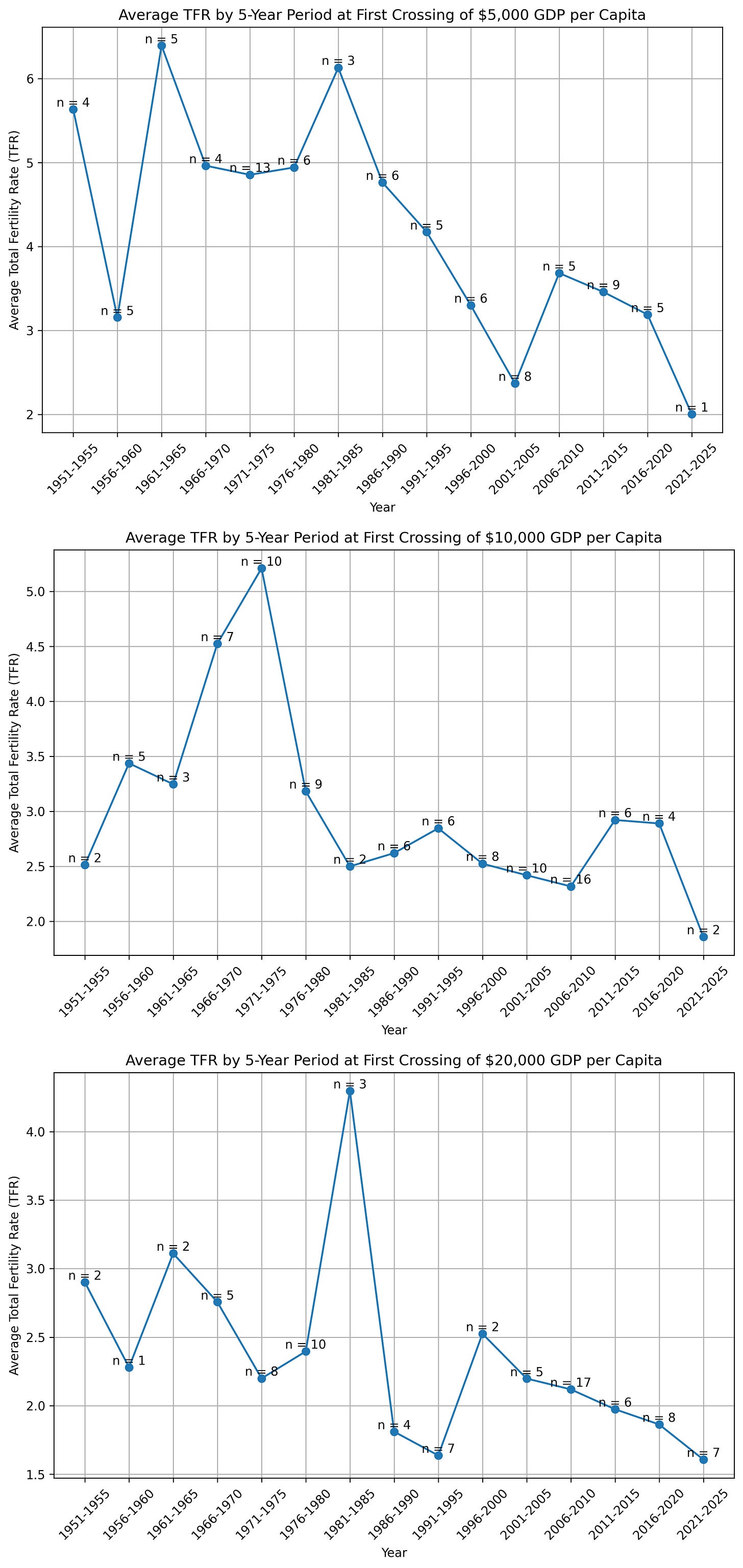

Here are some charts showing how the relationship between TFR and reaching the thresholds of $5K, $10K, and $20K grouped by five-year periods. We see clear declines at each level.

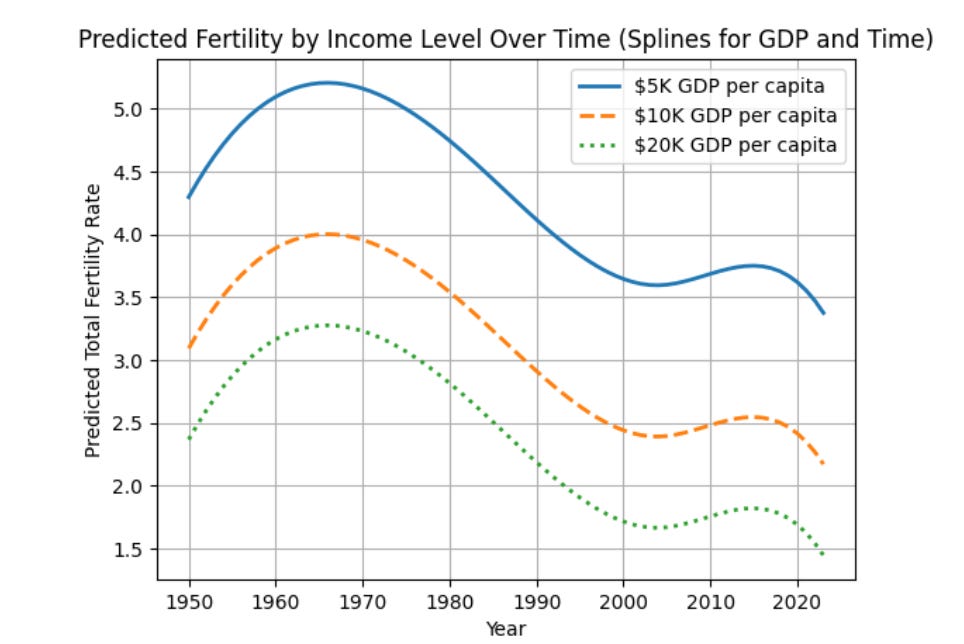

Below is a graph showing predicted fertility by year at GDP per capita levels of $5K, $10K, and $20K. I estimate the parameters of a model using all country-years to predict total fertility rate from log GDP per capita, year, and a dummy variable for oil-rich Arab countries plus Brunei, which in effect excludes them from the analysis. Rather than imposing linear effects, I model both income and time using cubic spline basis functions with five degrees of freedom, which allows the relationships between fertility, income, and time to vary smoothly across income levels and historical periods.

From 1950 to the early 2020s, a country at each income threshold ends up having about one less child per woman.

What explains this pattern? We can start with a simple opportunity costs model. When you’re richer, the alternatives to having children get much better. If your labor is worth $10K a year, focusing on raising kids is less likely to be seen as worthwhile than if it is worth $20K a year. But $20K a year in 2025 will get you a smartphone, which you couldn’t have no matter how rich you were in 1980. About two-thirds of people today have smartphones in middle-income countries like China, Brazil, and Indonesia. US GDP per capita passed $20K all the way back in 1955. If you wanted to have fun at that time, you could listen to the radio or watch one of three television stations available, but other than that, you needed to go outside to enjoy yourself. Maybe you’d play a sport with neighbors, or go to a diner, or a drive-in movie. The US in 1955 was about as wealthy as Paraguay or Kosovo today, but modern nations with equivalent levels of wealth have access to things like the internet and streaming video services.

In the early 1970s, TFR in France hovered around 2.5, as GDP was about $20K a year. Today, Brazil and China are about as wealthy, but have TFRs of 1.6 and 1 respectively. The US experienced a baby boom from around 1946 to 1970. The data only begins in 1950, but if you start there and look at the next twenty years, the US averaged 3.3 children per woman. During that time, GDP per capita increased 60%, which is truly remarkable since this was happening even as the population was growing rapidly. It’s practically unheard of today for a country at 1960s American levels of wealth to maintain a fertility rate of over 3 unless it is Muslim or a state that got rich primarily through resource extraction and maintains a more traditional culture. It’s remarkable to think that during the tail end of the baby boom, the US was 40% wealthier than modern China while having over two and a half times more children per woman!

Phones can’t be the entire story, as we’ve seen the decline in fertility while controlling for wealth going back half a century. Things have gotten worse since smartphones, but they were getting worse before that too. Perhaps they are just the latest in a series of new technologies that isolate people from one another and give them reasons to stay inside. Before smartphones, there were radio, record players, CDs, personal computers, TV, color TV, cable, video games, etc.

Another way to look at this perhaps is that matching countries according to GDP over time is comparing apples to oranges. Is an American in 1960 really as wealthy as a Chinese person today? There is an endless list of products and services that a Chinese person today can enjoy that didn’t even exist more than half a century ago. Our numbers may not do a very good job of capturing the consumer surplus we get from the internet and other recently available goods and services. In practical terms, however, this boils down to the same thing as the idea that technology has pushed us in an anti-natalist direction. We can say fertility has fallen given measured GDP over time either 1) because we’re actually much wealthier today compared to the past than GDP matching suggests, or 2) because technology has changed what life is like over time even controlling for levels of wealth. These are in the end the same theory for our purposes.

Another theory we might put forward is that there’s a global culture that has become more anti-family and anti-child over time. This can’t be easily separated from the technology question, since TV and the internet are methods through which ideas spread. Because fertility controlling for income was already dropping throughout the 1980s and 1990s, there was probably something cultural going on here that isn’t easy to quantify.

There’s a very famous 2012 paper on Brazil by La Ferrara et al. that demonstrates the connection between forms of entertainment and culture. Between 1970 and 1991, the share of Brazilians with a television went from 8% to 81%. During that same period, TFR declined from 5.8 births per woman to 2.9. Interestingly, Brazil also remained highly uneducated during this era, with literacy only reaching about 80% in the early 1990s. Rede Globo is the largest television channel in the country, and its soap operas that feature small families and stress emancipatory values have massive audiences. Television licenses for different regions were historically given out by the government based on political or ideological reasons, allowing La Ferrara et al to treat access to popular soap operas in an area as somewhat random, of course controlling for other factors that might affect fertility. They attribute about 7 percent of the reduction in the probability of giving birth in Brazil between 1980 and 1991 to the reach of Rede Globo alone.

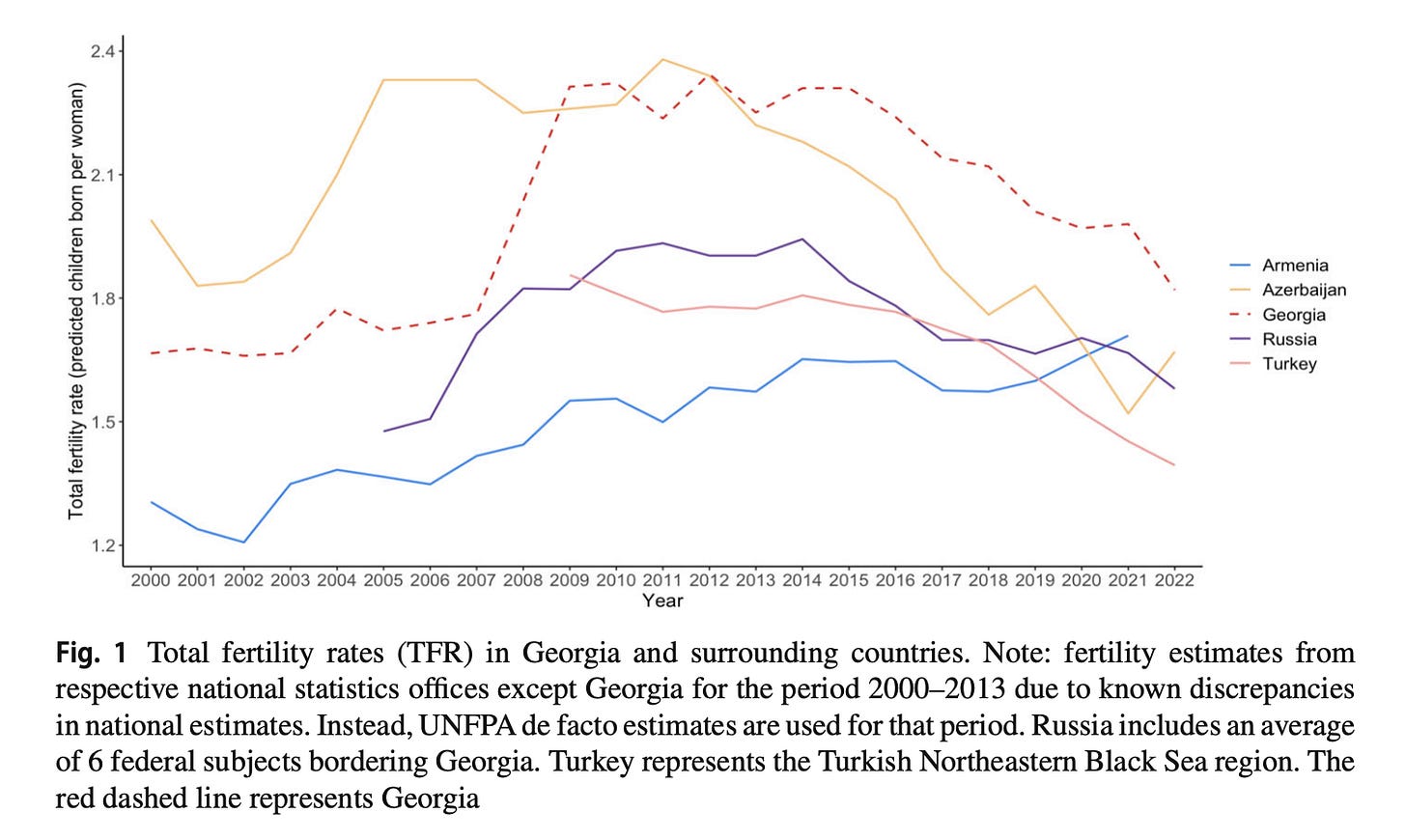

Do we have examples of culture shifting in the opposite direction? Perhaps the most interesting story showing the impact of ideas is when in late 2007 the Georgian Patriarch Ilia II promised to personally baptize any baby born into a family that already had two or more children. The chart below shows Georgian fertility over time, compared to neighboring countries and bordering regions in Russia and Turkey.

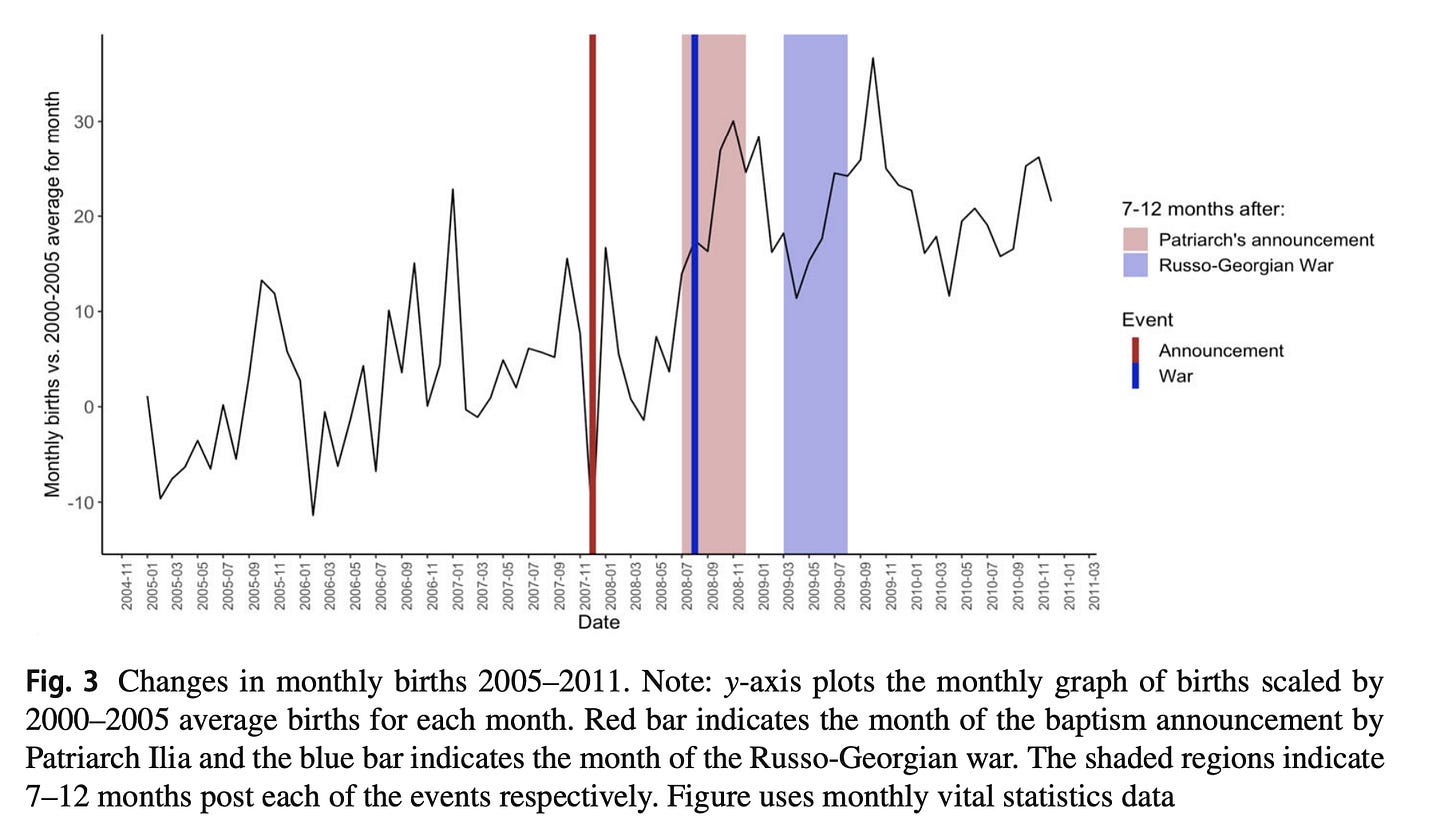

I’ve always been fascinated by this story, since the causal mechanism is so simple and straightforward. Chung et al. track fertility month by month and see a boost literally nine months after the patriarch’s announcement.

This worked in Georgia because the population at the time of the baptism announcement was less than four million. As of 2024, Patriarch Ilia had over 48,000 godchildren, often engaging in mass baptisms involving hundreds or thousands of babies. Over 16 years, that comes out to about eight kids a day. It’s probably less manageable for the Pope to promise the same to the world’s Catholics, unless he wanted to bless them all by Zoom, which seems like it would have much less of an effect.

Government policy might have a role to play in fixing the fertility issue, but in most countries culture seems more important. Brazil, for example, never engaged in family planning policies. It even made the advertising of contraception illegal until 1979, and abortion remains criminalized under most circumstances to this day. Nonetheless, fertility fell due to technological and cultural factors, despite the social conservatism of the Brazilian government throughout much of the last few decades. China and South Korea today are trying to encourage more births, and have had limited if any success.

Most of the evidence suggests we should be pessimistic about things turning around. Nonetheless, the lesson of Georgia is that social pressure works at least in some circumstances. We need to figure out whatever the equivalent of getting the Georgian Patriarch to baptize all third children is in other cultural contexts.

One thing I would say about the baby subsidies debate is that, from my perspective, at the point government is spending a lot of money on increasing births, it will indicate that the battle has largely been won. In a democracy, the state tries to do things that most people think are worth supporting. If we as a society were willing to spend on babies anywhere near as much as we spend on Social Security, then there would already be widespread consensus on the importance of having children. This is perhaps another reason to support pro-natalist policies. Whether or not it wins, partaking in this movement can increase the salience of the fertility issue and provide opportunities to convince people that creating new life is a good thing.

Source link