UK’s Jewish answer to Zohran Mamdani is now one of PM Keir Starmer’s biggest challenges

LONDON — Less than four months after being elected leader of the Green Party, Zack Polanski, is fast emerging as Britain’s most prominent Jewish politician — and the standard-bearer for the country’s newly energized radical left.

Young, gay and vegan, Polanski, 43, is snapping at the governing Labour party’s heels in the polls, his ascent fueled by a Zohran Mamdani-like cocktail of promises to soak the rich and expand the government, married to an anti-Israel, identity politics agenda.

“I take huge inspiration from Mamdani,” Polanski proudly declared after the election of New York’s new mayor.

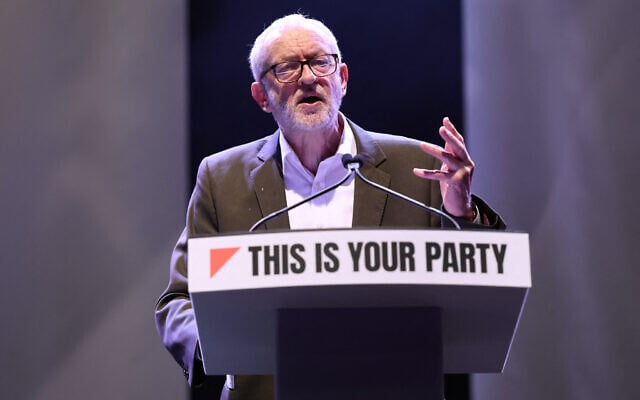

Polanski’s rise has also stymied the launch of Jeremy Corbyn’s new far-left party, which has been riven by infighting between allies of the disgraced former Labour leader.

And the Greens’ ascent is increasing pressure on Prime Minister Keir Starmer to tack to the left to stem the bleeding of its supporters to Polanski’s party.

Amid a dizzying array of U-turns, anaemic economic growth and soaring taxes, and talk of a leadership challenge to Starmer, Labour’s support has sunk in the polls. The Conservatives’ historic defeat last July means they remain in the doghouse in many voters’ eyes. Instead, led by Nigel Farage — a populist libertarian who led the successful campaign for Brexit — the insurgent right-wing Reform UK is making the political weather.

But while Farage mops up disenchanted Tories and chips away at Labour’s traditional working-class support in the “red wall” constituencies of the north of England, Polanski is winning the backing of younger voters, especially in the UK’s left-leaning big cities.

A former actor-turned-hypnotherapist, Polanski defected from the centrist Liberal Democrats to the Greens in 2017. He was subsequently elected to the London Assembly, to which the capital’s mayor is answerable, and elected Green Party deputy leader. This summer, he campaigned for the top job, using his successful run for the party’s leadership to cast himself as the anti-Farage, while promoting an approach he dubs “eco populism.”

Polanski’s strategy makes good electoral sense. At the last general election, the Greens came in second for 40 parliamentary seats; all of them are held by Labour and most in the party’s urban, graduate-heavy strongholds, including London, Manchester, Leeds and Merseyside.

A radical agenda

If not entirely absent, the Greens’ traditional pitch on climate change has been relegated to the backseat. In its place, Polanski has adopted a message which combines class warfare and ultra-progressivism, arguing: “There is no environmental justice without racial, social and economic justice.”

Wealth and inequality, not climate change, were the centrepiece of his address to the Green Party’s annual conference in October. Claiming that the UK is a country where “a tiny few have taken our power, our wealth,” he declared it is “time to take it back,” by introducing a wealth tax on the “super rich” and ending the “failed experiment” of privatization. The Greens want to nationalize the utility companies, establish a state-owned housebuilder and cap high salaries. “We don’t need to tax and spend,” Polanski told the BBC in September. “We need to spend and tax.”

At a time when public concern about immigration tops the polls, Polanski is “unapologetically very pro-migration.” And, placing himself front and center of Britain’s culture wars, he described the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling this spring, which defined women by their biological sex rather than their gender identity, as “thinly veiled transphobia” and pledged to “support our trans siblings unconditionally.”

Polanski opposes the government’s increase in defense spending (the Greens have long opposed Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent) and toyed with the UK leaving NATO during the leadership campaign. Last month, he sparked an incredulous reaction from a TV interviewer when he said he would ask the Russian president to give up his nuclear weapons.

While Polanski terms Farage a “Trump-loving, tax-avoiding, science-denying, NHS-dismantling corporate stooge,” Starmer’s Labour is the main focus of his attacks. “When Farage says jump, Labour [says] ‘how high,’” he says, accusing Starmer of “[creating] the circumstances for the far right to rise” by “protecting the wealth and power of the super rich.”

But it is Labour’s supposed support for Israel which has most provoked Polanski’s ire. In his keynote speech to the Green conference in October, the party’s new leader made no mention of Iran, China or Russia — the only mention of Ukraine was a passing reference to his Jewish ancestry — while devoting several passages to Gaza.

After assailing Israel’s “mass slaughter” and “genocide” in Palestine, he railed against Starmer’s government, which he labeled “an active participant in the murdering of the Palestinians.” Polanski went on to reiterate the Greens’ calls for a complete arms embargo on Israel, an end to intelligence sharing and a lifting of the ban on the extremist group Palestine Action.

Polanski, who has repeatedly called for the arrest of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and condemned Israel’s “horrendous and illegal” airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs in June, says he grew up in a “very Zionist” household and was raised to believe the Jewish state was “the center of everything” and “must be defended at all costs.” But “Israel has changed,” claims Polanski, who says he is “certainly not a Zionist.”

As he has adopted a more hardline position on Israel, Polanski also appears to have shifted his stance on what he considers to be antisemitism. He has recanted his past criticism of the antisemitism scandal which roiled Labour under Starmer’s hard-left predecessor, Jeremy Corbyn. He now claims it was “blatantly not true” that the party had been “rife” with antisemitism and that he had been wrong to criticize it.

Polanski’s anti-Zionist stance doesn’t represent a radical break with the Greens’ historic hostility towards the Jewish state.

Polanski’s response to media revelations about antisemitism within the Green Party during last year’s general election was to warn against “the conflation between legitimate criticism of the Israeli government and antisemitism” while accusing other parties of “weaponizing” the issue.

As Polanski has acknowledged, progressive voters’ belief that Labour has not been tough enough on Israel has won the Greens additional support.

But Polanski’s anti-Zionist stance doesn’t represent a radical break with the Greens’ historic hostility towards the Jewish state. According to Dr. James Vaughan, an expert in UK-Israel relations at the University of Aberystwyth’s department of international politics, as far back as 1990, a senior Green Party member was reportedly arguing that there was “no Green justification for Israel’s existence at all.” Well over a decade ago, a report commissioned by the Green Party Regional Council expressed concern about a tendency for anti-Israeli activism to slide towards a tolerance for low-level antisemitism.

“In that sense, the positioning of the Green Party under Polanski’s leadership isn’t especially new, it is simply operating in a much more favorable political climate where previously marginal views about the illegitimacy of Zionism are becoming more widely accepted and normalized,” says Vaughan.

Polanski’s style of politics is grabbing as much, if not more, attention as the substance of his policies. Articulate, charming and personable, he delivers his message without the air of menace and moral superiority that has traditionally limited the electoral appeal of the hard left. His hyperactive and social media-savvy style of leadership is already bearing fruit. Polanski has over 100,000 followers on TikTok (double that of Starmer) and 500,000 on Instagram. Shortly after winning the Green leadership, he launched his own weekly podcast, “Bold Politics.”

Under the new slogan ‘make hope normal again,’ the Greens’ membership has risen from under 70,000 earlier this year to 184,000 in December — overtaking both the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives.

Under the new slogan “make hope normal again,” the Greens’ membership has risen from under 70,000 earlier this year to 184,000 in December — overtaking both the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives — and the party is polling higher than ever before, with some surveys showing it pulling level with Labour. Polling in October indicated that 15% of those who backed Labour last July now say they will switch to the Greens. The polls also show the Greens gaining strongly in London, a Labour stronghold, and beating Starmer’s party among young people by 25 points.

Prof. Glen O’Hara, a professor of modern and contemporary history at Oxford Brookes University, terms Polanski “the most dangerous opponent Labour has faced on its left flank for decades.”

“Polanski is a skilled operator who tells liberal, outward-looking Britain exactly what it wants to hear. On government spending, immigration, public services and the like, he speaks exactly the language of the progressive middle classes, disillusioned by Starmer’s turn towards placating Reform UK voters,” says O’Hara. “Polanski’s already started to moderate his left-wing language to some extent, so as to widen his appeal.”

The Your Party farce

Polanski has also successfully blunted Corbyn’s hopes to capitalize on Labour’s unpopularity by providing a new political home for left-wing Britons.

Polanski, who has previously said he would welcome Corbyn into the Greens’ ranks, has been helped by the chaotic launch of Corbyn’s socialist Your Party and bitter squabbling among its founding members.

Corbyn, who was kicked out of Labour by Starmer following a scandal over antisemitism in the party under his watch and reelected to parliament last July as an independent, began making his initial moves to form a new left-wing party earlier this summer. He quickly succeeded in winning the backing of the Independent Alliance, a grouping of pro-Gaza MPs who seized four heavily Muslim seats from Labour at the general election.

But relations between Corbyn and Zarah Sultana, a young Muslim MP who shares his far-left, anti-Israel politics, have been strained from the outset. First elected to the House of Commons in 2019, Sultana was suspended from the parliamentary Labour Party shortly after the general election for rebelling against the new government in a vote on welfare policies.

Having formally resigned her Labour membership in July, Sultana immediately declared she was launching a new party with Corbyn. The announcement appeared to take Corbyn by surprise, and he immediately signalled his irritation. When the party’s website was formally launched several weeks later, the pair couldn’t even agree on a name. Corbyn referred to it as “Your Party,” while Sultana said that wouldn’t be the new entity’s name and that she preferred “the Left Party.” The decision was deferred with an agreement that members would vote on the party’s new name at an inaugural conference in the autumn. (They chose to stick with Your Party).

Your Party is a coalition of far-left factions and egos who can’t stop fighting each other.

The perception that Your Party had descended into the realms of political farce was compounded in September when, just as Polanski was gaining momentum following his election as leader, Corbyn and Sultana began a new squabble over the launch of its membership portal. Sultana claimed the new party was being run as a “sexist boys’ club,” while Corbyn said he was seeking legal advice.

A more substantive clash within the party over the issue of trans rights came after Adnan Hussain, one of the pro-Gaza independent MPs who had joined Your Party, said that “women’s rights and safe spaces should not be encroached upon.” Sultana, a strong supporter of trans rights, hit back, saying: “Trans rights are human rights. Your Party will defend them — no ifs, no buts.”

Hussain later quit the party, blaming “persistent infighting” and alleging prejudice towards Muslim MPs within the group. Days later, another of the pro-Gaza MPs, Iqbal Mohamed, followed Hussain out of the door, citing “false allegations and smears made against me and others.”

Nor did matters improve when Your Party’s launch conference at the end of last month began with the expulsion of several members who were found to also be members of other far-left parties, including the Socialist Workers Party. While Corbyn opened the event with a call for “unity” and led a chant of “free, free Palestine,” Sultana — who boycotted the opening day — railed against “a culture of witch-hunts” in Your Party, which had led to “bullying, intimidation and smears,” and “acts of deliberate sabotage.” The party also voted not to have a single leader, but to have a collective leadership, with a chairperson drawn from outside parliament.

“Your Party is a coalition of far-left factions and egos who can’t stop fighting each other,” says Alex Hearn, director of the campaign group Labour Against Antisemitism. “Voters have watched them botch everything from data management to their own party name.”

Nonetheless, Hearn says, “the chaos goes deeper than organizational incompetence.”

“They’re trying to hold together an impossible alliance of hard-left activists, socially conservative Muslims and campaigners on subjects such as trans rights,” he says. “Beyond Gaza, they’re worlds apart.”

But Polanski hasn’t cornered the political space to Labour’s left simply due to Your Party’s failings.

“The Greens know exactly what they stand for,” Hearn says. “United behind a charismatic populist who understands messaging, the climate emergency has taken a back seat compared to ‘the genocide in Gaza.’ They’ve repositioned themselves as Labour’s socialist alternative, with Polanski’s populist appeal to the left mirroring Reform’s appeal to the right.”

Unlike Your Party, says Hearn, the Greens are “organized and disciplined enough to make it work.”