For decades, libraries served as a safe haven for many queer and marginalized youths in eastern Texas, says former county library director Rhea Young. Unlike the school cafeteria, the library was a space where they could explore and find acceptance in who they wanted to be.

“There were books where they can find characters like them, and realize it’s okay to be who they are,” Young said. “There needs to be more places like that, not fewer.”

That all changed two summers ago when, amid a wave of book bans, Montgomery county officials asked Young to move books with LGBTQ+ themes or “sexually explicit” content at the public library into a section restricted to readers 18 years and older, and instructed her to order more titles with conservative Christian content.

One of the books she was told to pull was It’s Perfectly Normal, the popular illustrated book that teaches children about puberty, sex and sexuality. Young had bought the book for her own 10-year-old son two decades ago when he expressed curiosity about his changing body. She said it later helped him come to terms with his identity as a transgender man.

But Young decided that she couldn’t follow a policy that devalued the experiences of her son and other marginalized children and teens.

In January, Young was fired, in what she felt was retaliation for refusing to impose the county’s political agenda. Seven months later, she fought back again: this time suing the county judge and commissioners for wrongful termination.

“I was pretty majorly depressed and angry,” Young said. “They took who I was away from me.”

As the culture wars descended on America’s public libraries, librarians like Young have moved to the frontlines of a battle to protect free speech and LGTBQ+ rights. In at least half a dozen states, they have joined forces with civil rights groups to oppose book bans, often facing personal and professional repercussions. Some of their legal challenges and victories, organizers and experts say, can provide a roadmap for grassroots resistance against coordinated censorship campaigns.

In October, Wyoming library director Terri Lesley won a $700,000 settlement after a yearslong dispute with officials in deeply conservative Campbell county. After refusing orders to remove books like Cory Silverberg’s Sex is a Funny Word and Juno Dawson’s This Book Is Gay – two queer-inclusive sex ed books – from the children’s collection, Lesley said she lost her job and was repeatedly labeled “pedophile” and “groomer” by conservative activists.

A librarian for 27 years, Lesley said she’d considered herself more a public servant than a political organizer.

“I felt that I had to stand up for the LGBTQ+ community,” she said. “We all have the right to read the things we choose to read. I can’t imagine taking that away from any individual.”

A ‘manufactured crisis’

Iris Halpern, the attorney representing Lesley and Young, said these legal challenges should give county officials pause before retaliating against librarians for expressing their first amendment rights. Halpern said her firm has filed litigation on five wrongful termination cases and is actively monitoring three others.

“We all hope it sends a message out that you should not discriminate against constituents you represent, that there will be ramifications if you break the law,” she said.

In the first half of the year, state lawmakers introduced more than 130 bills to restrict access to library materials and impose harsh penalties on non-compliant librarians. The American Library Association recorded 821 attempts to ban library books and services in 2024 – the third-highest year on record. More than two-thirds of documented attempts were initiated by special interest groups and elected officials, the organization found.

“This has been indicative of censorship matters of the past 5 years,” said Sam Helmick, the president of ALA. “Despite 70% of Americans not wanting censorship in any way, we still have representatives who no longer trust the community to make those decisions for themselves and their families.”

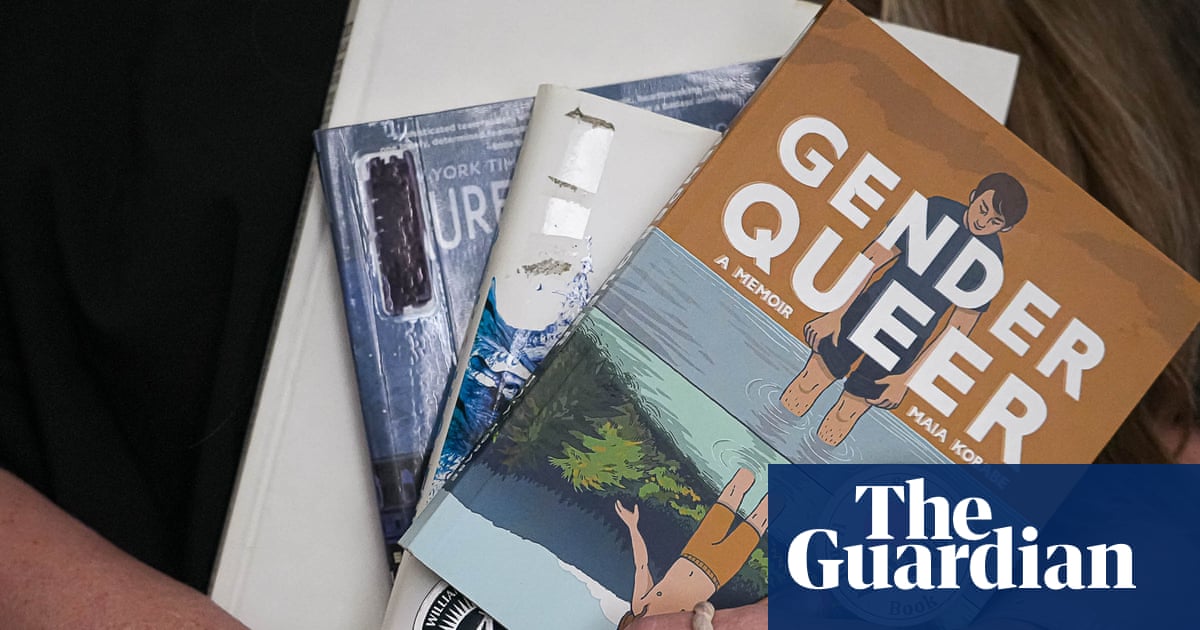

Books exploring race, sexual health and gender identity have faced an unprecedented level of challenges in recent years, as Republican-led states sought to codify censorship into law. Award-winning books such as Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me have all been caught in the crosshairs.

In public schools, the majority of banned books last year featured people of color, LGBTQ+ people and other demographics, according to a PEN America report. In Greenville county, South Carolina, a group of library patrons sued in March to block book restriction policies that purged at least 59 titles by or about LGBTQ+ people. The case is still pending in federal court.

Halpern said the surge in book bans is a “manufactured crisis” fueled by national conservative groups such as Moms for Liberty and the National Federation of Republican Women. Local chapters of both organizations have challenged dozens of books in public and school libraries.

“These organizations have fine-tuned the blueprint for ways to attack LGBTQ+ rights, to attack information on racial history, slavery and discrimination, all while outside funding local elections,” Halpern said.

‘The library is the purest form of democracy’

In April, Texas librarian Suzette Baker won a $225,000 settlement after she was fired from a Llano county library a year earlier. One of her final acts, she said, had been putting up a public display of titles the county wanted banned, including the humorous children’s book I Broke My Butt.

Baker’s firing inspired a group of library patrons and local parents to file a separate lawsuit against the county’s book removal efforts. An appeals court dealt a blow to the residents – and the movement at large – by ruling in favor of county officials and allowing the bans to take place. The supreme court this week declined to review the case.

As an army veteran, Baker said she knew what it meant to take an oath to protect the constitution – a requirement for both service members and librarians – and curtailing people’s right to read is a violation of that oath.

“We have freedoms in this country,” she said. “They’re being infringed, taken away from us, left and right now.”

The costs of fighting for those freedoms have been steep. No library nearby would hire her, Baker said. Until she won the settlement, she’d been working as a cashier at a hardware store while caring for her disabled adult son.

In some cases, librarians have taken on local governments and won. In Huntington Beach, a rare Republican bastion in deep blue California, former librarian Erin Spivey became the spokesperson of a grassroots movement against the city’s efforts to restrict children’s access to books with so-called “sexual content”. This nebulous, overly broad definition meant that banned books included one about a dog at a pride parade (“Pride Puppy!”) and another about potty training (“Once Upon a Potty”).

When the city passed its book restriction law in 2023, Spivey immediately began reaching out to lawyers who specialized in first amendment cases to challenge the policy. Fighting against book censorship is crucial to protecting the reputation of a sacred institution, she said.

“I’ve always felt like the library is the purest form of democracy,” said Spivey, 45. “Every single person who walks through that door is equal to every other person in that building.”

Spivey said the attorneys who took on her case were concerned about filing a federal lawsuit that could end up in front of the conservative supreme court. Instead, Spivey and the ACLU worked with state legislators to push through the California Freedom to Read Act, which barred book bans based on the views of the material or author. In February, a month after the law went into effect, Spivey and the ACLU sued Huntington Beach, and the city’s censorship policy was struck down. (The city has since appealed the ruling.)

Jonathan Markovitz, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU Foundation of Southern California who worked on Spivey’s case, said the ongoing legal battles against book bans can be considered “complementary ways of fighting back against censorship”.

As the ACLU fought Huntington Beach’s censorship scheme in court, Markovitz said, hundreds of residents mobilized and passed a ballot measure that undermined the city’s power to remove library books. (The ACLU is actively involved in multiple major lawsuits against book bans.)

“If there is a need for similar suits around the country going forward, I hope that the lawyers who file them will be attentive to community needs and will work with, or alongside, grassroots activists,” he said. “And I hope those activists will find value and inspiration in the lawsuits.”

Source link