FARGO, N.D. — Conserving, protecting and utilizing soil matters to producers. That was evident at the University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University Soil Management Summit and Dakota Innovation Research and Technology Conference, which joined together in Fargo and drew a significantly larger crowd than expected.

Nearly 350 attendees came to learn about soil health practices as well as learn new skills to put soil conservation practices to work in their fields. One of those sessions was packed with producers and conservation staff eager to hear an important question answered: Do you need cost-share programs to make soil health pay?

The answer — as is often the case in farming — was “sometimes” according to Samuel Porter, a Minnesota Farmers Union agricultural research economist. He included with that an entire presentation on research that shows what the most profitable farmers are doing right.

Porter said people generally fall into two groups: those who decide to do something new when times get tough and those who are determined to change nothing in those hard times.

Trying out something that “might work” is a risk. The current environment of high input costs and low commodity prices is forcing producers to either cut anything unnecessary or try something that could replace some of those input costs.

At nearly all of the sessions, cover crops were at least part of the conversation. But Porter cautions producers from simply deciding to add cover crops without defining how that is going to be used as a management tool.

“I think it would be a mistake to do it because it sounds good,” Porter said.

Michael Johnson / Agweek

Some management goals may be to reduce erosion or compaction; improve infiltration, soil structure, and water holding capacity; pest management; improve soil organic matter; weed suppression; reduce inputs; and support yield risk and stability.

“Just doing these for the heck of it will certainly not pay for itself,” Porter said.

What producers should also weigh are the internal and external benefits. Things like erosion control can benefit your farm and the public if your highly valuable soil and nutrients leave your farm and end up where someone else does not want them. As one farmer explained, losing the fertile soil is more than just a one-time loss; it’s a loss of a legacy built for generations and a loss for generations to come. He asked what kind of dollar amount could be placed on that.

Water management can mean you get into the field earlier, allowing for more growing degree days and timely applications. Long-term fertilizer reduction can be a major cost savings and a benefit in areas where excess nutrient runoff is an issue.

“When you’re itching, what are you going to pay to get out there sooner? Would you pay $5 an acre to get out there sooner? What are you going to pay? Think about that,” Porter said.

Not everyone who implements cover crops sees a reduction in fertilizer costs. A

National Cover Crop Survey

that Porter referenced showed that out of 272 respondents, the majority, 141, saw no change in costs. However, 58 saved more than $20 an acre, more than any that saw increased costs.

University of Illinois research showed that corn fields without cover crops averaged higher yields (215) compared to those with cover crops (206). However, Porter pointed out that cover crops offered more stability as the fields with the lowest yields (average 147 bushels) had higher yields when using cover crops (average 159 bushels).

Likewise, incorporating no-till and cover crops or no-till and no cover crops offered more stability than conventional tillage with no cover crops, which experienced the highest highs under the right conditions and lowest lows during less than ideal conditions, according to a 2020

University of Nebraska study.

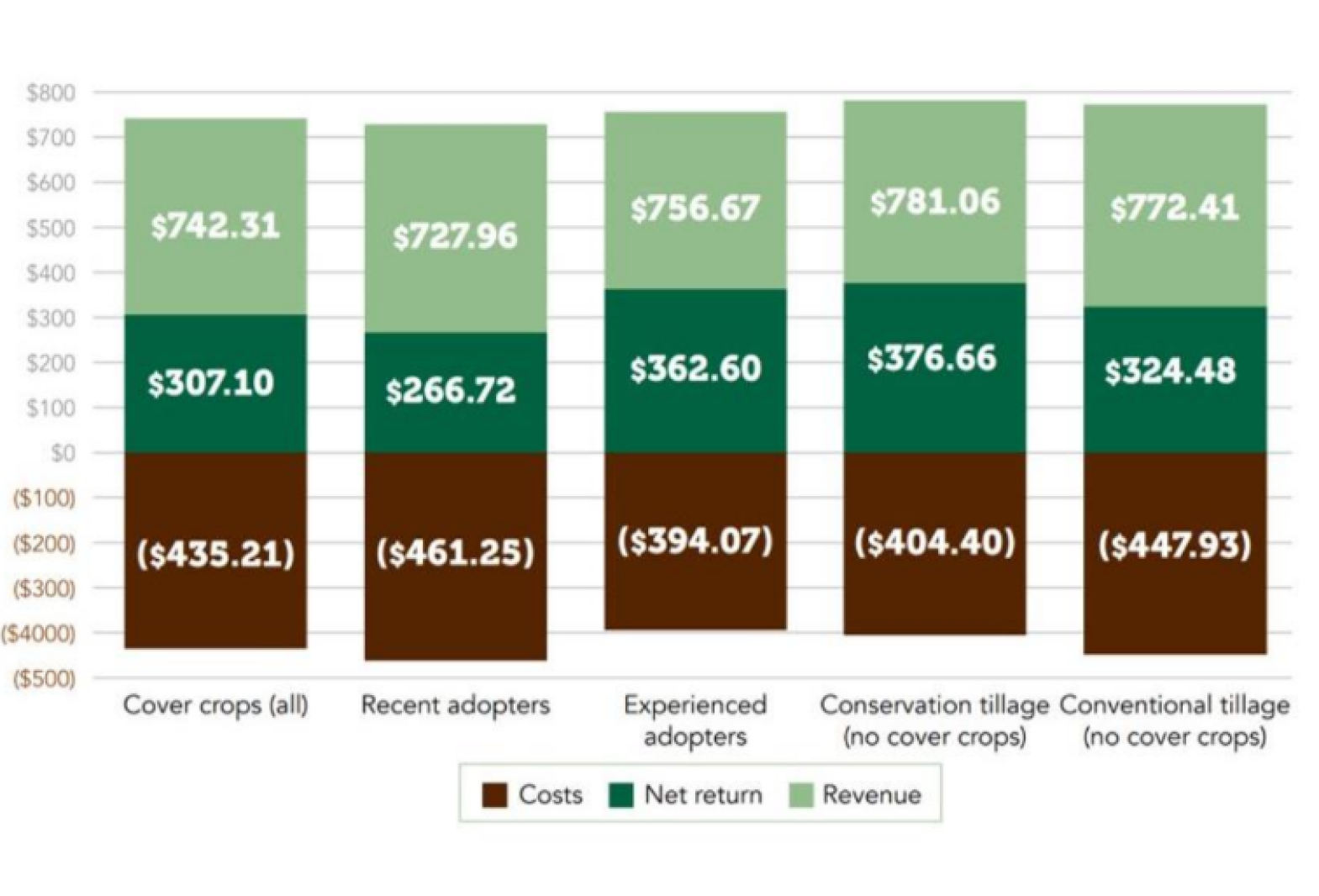

One piece of research that Porter found fascinating is that there is a major profitability difference between those who recently adopted conservation practices and those who are experienced. Net return for the recent adopter was $266.72. That was the lowest return among those using cover crops, experienced adopters, conservation tillage without cover crops and conventional tillage without cover crops. Some producers might feel ready to get out after that initial lower profit. Porter said research shows it’s worth keeping after it.

The experienced adopters had one of the highest returns at $362.60 per acre. That was higher than conventional tillage ($324.48) and just lower than conservation tillage ($376.66), which had the highest net return. The experienced adopters had the lowest costs.

“I think reduced tillage has shown that yields remain high and it can reduce costs and it just makes a lot of sense,” Porter said. Pairing cover crops with reduced tillage can help reduce soil compaction, which has its own benefits. “So thinking about the whole system and building healthy soil is part of how we get there.”

Something not taken into consideration is time management, simply because most farmers generally do not track the time they put into their farm, Porter said. Practices like reduced tillage, reduced inputs and reduced water usage can all free up a farmer’s time. Porter wondered if a producer could put a value on having a few extra hours to spend with family or perhaps to work on some other put-off project on the farm.

And for those who are using cost-sharing benefits to pay for cover crop of tillage practices, Porter explained that existing programs like the Natural Resources Conservation Service payments for

EQIP

do pay to use. In Minnesota, those

NRCS payments

for cover crops are $74.72 an acre and residue and tillage management were worth $24.29 an acre. Those payments are just slightly lower for North Dakota producers.

“You’re making money if you’re doing that, as far as I’m concerned,” Porter said.

A study of those who utilize cost-share programs showed that users are likely to continue to adopt the practices if they are successful in planting, if they have healthy emergence and if there is a lack of extreme weather. A higher payment was not a significant factor.

Porter shared a concern about a dependency forming for cost-share programs. He said it should be used to help with a transition or to get a start in these practices, but not for long-term use once the lessons of profitability have been learned. He added that if the cost is high, but the benefit goes far beyond your own farm, then the cost-share has its role.

“There is a role of financial assistance, but you don’t necessarily need it in order to be profitable, in order for you to get what you want,” Porter said.

He highlighted

Minnesota’s Soil Health Equipment grants

as an excellent opportunity to receive one-time funds to help share costs of eligible purchases of new or used equipment or parts for soil health practices, such as no-till or strip-tilling equipment.

Producers agreed it was valuable; however, the funding has so far been scooped up very quickly and does not cover the current pool of applicants. There is $4.36 million available for fiscal year 2026. Porter recommended producers call their lawmakers if they’d like to see those funds increased further.