POCATELLO — Local officials are mobilizing emergency response plans as Idaho’s elimination of specialized mental health programs takes effect, with law enforcement and service providers predicting immediate impacts on public safety and hospitals across East Idaho.

The cuts, which took effect Dec. 1, eliminated or significantly reduced six evidence-based programs serving approximately 1,000 of Idaho’s most severely mentally ill residents statewide — primarily individuals with schizophrenia or severe bipolar disorder — including an estimated 100 people in the Pocatello area said Ric Boyce, co-director of the Idaho Association of Community Providers and CEO of Pocatello-based Mental Health Specialists.

“In a single move, the state of Idaho has just removed all of the programs to treat the most acute individuals with mental illness in the state,” Boyce said.

Emergency meetings convened

Bannock County Emergency Management has convened two emergency planning meetings focused on responding to the mental health system changes. State Reps. Rick Cheatum, R-Pocatello, and Dan Garner, R-Clifton, attended the second meeting Thursday, “reflecting the degree to which these changes are now being treated as an emergency-planning issue at the local level,” Boyce said, adding that similar meetings have also been held in Idaho Falls recently.

Additionally, Pocatello Mayor Brian Blad sent a letter to Gov. Brad Little on Dec. 9 warning the cuts would impact public safety, emergency medical services, hospitals and local governments.

‘A preventable set of circumstances’

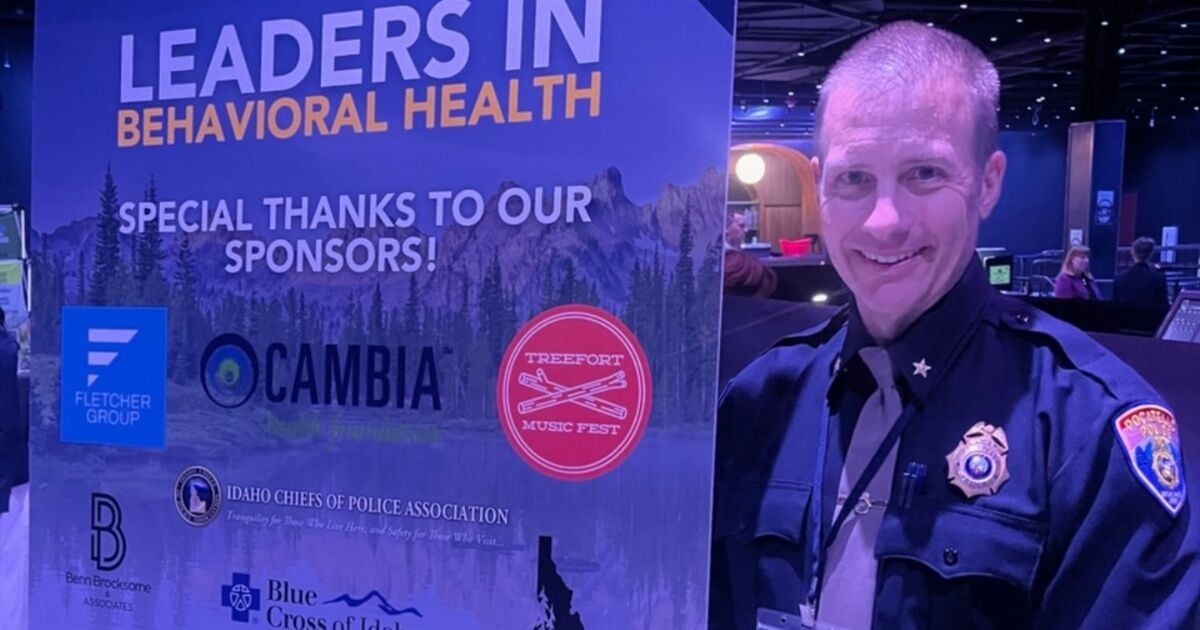

Pocatello Police Chief Roger Schei called the situation entirely avoidable and criticized state legislators for failing to consult with law enforcement before implementing the cuts.

“This is 100 percent a preventable set of circumstances,” Schei said. “I hate it that it takes somebody getting hurt, or a travesty in the community, for things to change.”

Neither the Idaho Sheriffs’ Association, which issued a warning to Little and Republican lawmakers earlier this month, nor the Idaho Chiefs of Police Association were contacted about the decision, he said.

“No one reached out to us to ask what our thoughts were on how this is going to impact us,” Schei said. “This is very frustrating, because when you look at what the national outcry is, the police should not be dealing with mental health, and I 100 percent agree with that. But then these cuts throw more back onto the police, and we’re always the bad guy.”

Bannock County Sheriff Tony Manu warned the cuts would place additional burden on local law enforcement, jails and hospitals.

Tony Manu

“If you strip away more resources, that just puts more burden on the local government here, between county, city and our local resources,” Manu said. “I think it’ll put more demand on law enforcement out on the streets to deal with some of these individuals that have been under care.”

He expressed particular concern about people who require constant supervision to stay on their medications.

“There’s a certain population that isn’t able to monitor their medications on their own,” Manu said. “They need supervision from people who will make sure that they’re staying on their medications.”

Budget cuts follow privatization

The eliminated programs had been operated directly by the state for approximately 40 years before being privatized in 2024. When the state privatized the Assertive Community Treatment program, it simultaneously laid off all remaining state-run high-acuity stabilization teams, according to a white paper prepared by the Idaho Association of Community Providers and the Idaho ACT Coalition. Idaho now has no state-operated high-acuity mental health infrastructure remaining.

The cuts stem from Little’s executive order issued in August, which directed nearly all state agencies to pursue 3 percent general fund holdbacks from their fiscal year 2026 appropriations.

A 3 percent budget holdback from the Medicaid appropriation would require a $29.8 million reduction in general funds, according to a court declaration by Sasha O’Connell, deputy director of the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare.

The department was already planning to request a $100 million supplemental appropriation because of increased health care costs. It ultimately needed $130.5 million in general funds to comply with the executive order.

To meet the mandate, the department submitted a budget request reflecting a 4 percent reduction in managed care capitation rates and rates for services paid through traditional fee-for-service Medicaid.

Magellan Healthcare, the managed care organization that administers the Idaho Behavioral Health Plan, notified Assertive Community Treatment providers on Oct. 31 that the ACT services bundled billing code would no longer be available effective Dec. 1.

Six programs eliminated or cut

The Assertive Community Treatment program, which serves approximately 400 people statewide with 50 in the Pocatello area, has been eliminated entirely. The program provided 24-hour wraparound services to the most treatment-resistant individuals with severe mental illness.

Ric Boyce

“We knock on their doors, we help make sure that they are staying on their medications and engaging with treatment where all other programs have failed,” Boyce said.

High Acuity Residential Treatment homes, known as HART homes like Bella-Nacole in Pocatello, have lost approximately 50 percent of their funding, eliminating the specialized mental health treatment component that distinguished them from standard residential facilities.

The Early Intervention for Serious Mental Illness program, which served 200 to 300 people ages 15-30 annually diagnosed with first-episode schizophrenia, has been eliminated.

“That program engages them and teaches them how to handle their illness and how to be successful in life, despite having that illness,” Boyce said.

The peer support program, which served 3,000 to 4,000 Idahoans, has been eliminated entirely. The program utilized individuals with a history of mental illness who are in recovery to provide direct services to people still struggling. The elimination resulted in 600 peer support workers being laid off, many of whom have been hospitalized since, Boyce said.

Partial hospitalization programs have been cut in half, with half-day programs eliminated entirely. The intensive outpatient day treatment program has faced 10 percent funding cuts and new limits on how long people can remain in the program.

Costs expected to far exceed savings

While the six programs cost approximately $20 million to operate, the Idaho Association of Community Providers estimates the cuts will transfer $150 million to $180 million in new public costs in the first year.

The breakdown includes $70 million to $85 million in new costs to hospitals and emergency rooms; $28 million to $38 million to police, sheriffs and courts; $30 million to $40 million to cities, counties, emergency medical services and crisis centers; and $12 million to $18 million to child welfare systems.

“These cuts are going to cost the state $150 million-plus when you factor in the transferred costs to hospitals, when you factor in the transferred costs of jails and police involvement and increase in child protection reports, all based upon hard national research,” Boyce said.

For the Pocatello and greater economic region, the Idaho Association of Community Providers estimated approximately $20 million in transferred costs.

Hospitals and jails brace for impact

The cuts are expected to cause immediate surges in emergency room visits and psychiatric hospitalizations.

“We’re going to see people moving in and out and in and out of the hospital,” Boyce said. “It’s going to lead to bed shortages, and it’s going to make it much harder for somebody going in with a heart attack or any other medical problem or any other mental health problem, to have access to the community hospitals.”

Manu expressed similar concerns.

“When you get hospitals constantly dealing with those patients, and it takes a long time to deal with those mentally ill patients, it will quickly fill the local hospitals’ ER rooms,” Manu said. “When you get the ER rooms full of mental health patients and you take enough beds, it will impact the people that need the ER for other medical purposes.”

Both Manu and Schei stressed that jails are not appropriate for people dealing with mental health crises.

“Jail is not a place to put people that are going through a mental health crisis,” Schei said. “This is a big cycle, and we’re taking a step backwards.”

Manu noted Bannock County has experienced fatal outcomes when mentally ill individuals are housed in jail facilities not designed for long-term mental health care. Responding to a question about Pocatello resident Lance Quick, 40, who died in the Bannock County Jail while experiencing a mental health crisis seven years ago this week, Manu said, “That’s always a concern with us in the jail. That’s always in the forefront, and that’s always a battle we face every day when we have that population in our facility for an extended amount of time.”

Individuals experiencing severe mental illness often cannot monitor their own medications and need constant supervision and treatment rather than confinement, he added.

“The kind of confinement that we have in jail is not conducive for a mental health patient, because the jail was never designed for that,” Manu said.

Lawsuit challenges cuts

Five Medicaid beneficiaries filed a class action lawsuit in federal court on Nov. 26 challenging the elimination of ACT services, arguing the cuts violate the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act.

U.S. District Judge Amanda K. Brailsford denied their request for a temporary restraining order on Dec. 1, and a hearing on a preliminary injunction was held Friday. The federal judge took the matter under advisement, according to court records.

Call for legislative action

Schei urged legislators to engage directly with their constituents before making policy decisions affecting mental health services.

“Get out and talk to your constituents,” Schei said. “Talk to the people that you represent. That’s their job. Their job is to not make decisions based on their personal beliefs. Their job is to get out and talk to their constituents.”

Boyce said he has spent recent weeks meeting with legislators, Little’s office, and city and county officials across Idaho to address the crisis. He has met with officials in Meridian and Boise while also engaging with emergency management officials and school principals throughout Bannock County.

State Reps. Tonya Burgoyne and Marco Erickson visited the Bella-Nacole HART home and met directly with two residents this week.

“Both residents shared personal accounts of long histories of severe mental illness and the stability and recovery they have achieved through high-acuity residential treatment,” Boyce wrote in his Dec. 18 email. “The meeting provided a direct view into what these programs have meant for individuals whose needs have historically required intensive, long-term care.”

During discussions, Magellan referenced the availability of services such as treatment coordination phone lines, temporary mobile crisis responses and same-day crisis centers as options to mitigate impact, Boyce said.

“These references occurred alongside the closure of ACT teams and HART homes — programs designed to provide daily, intensive treatment and sustained stabilization for individuals with the most severe mental illness,” Boyce wrote.

The state’s projected budget deficit follows the Legislature and Little approving $450 million in tax cuts during the 2025 legislative session, after years of income tax cuts that have reduced the state’s revenue by $4 billion, the Idaho Capital Sun previously reported.

Source link