Forgotten bottles uncovered Denmark’s early butter production methods. DNA analysis revealed both beneficial and harmful bacteria.

Two long-forgotten bottles stored in a Frederiksberg basement since the 1890s have given researchers at the University of Copenhagen a rare glimpse into Denmark’s butter-making past. By applying modern DNA analysis, the team was able to study the contents of the bottles, uncovering unexpected bacterial traces and a reminder of the hygiene challenges faced during that era.

Today, billions of lactic acid bacteria are consumed daily in foods like yogurt, cheese, sausage, and even cold soups. These microbes have been essential for centuries in enhancing flavor and preserving food by acidifying it and suppressing harmful bacteria. Denmark was an early pioneer in harnessing lactic acid bacteria on an industrial scale, and when combined with the practice of pasteurization, this innovation improved the safety and quality of dairy products while reducing the risk of disease.

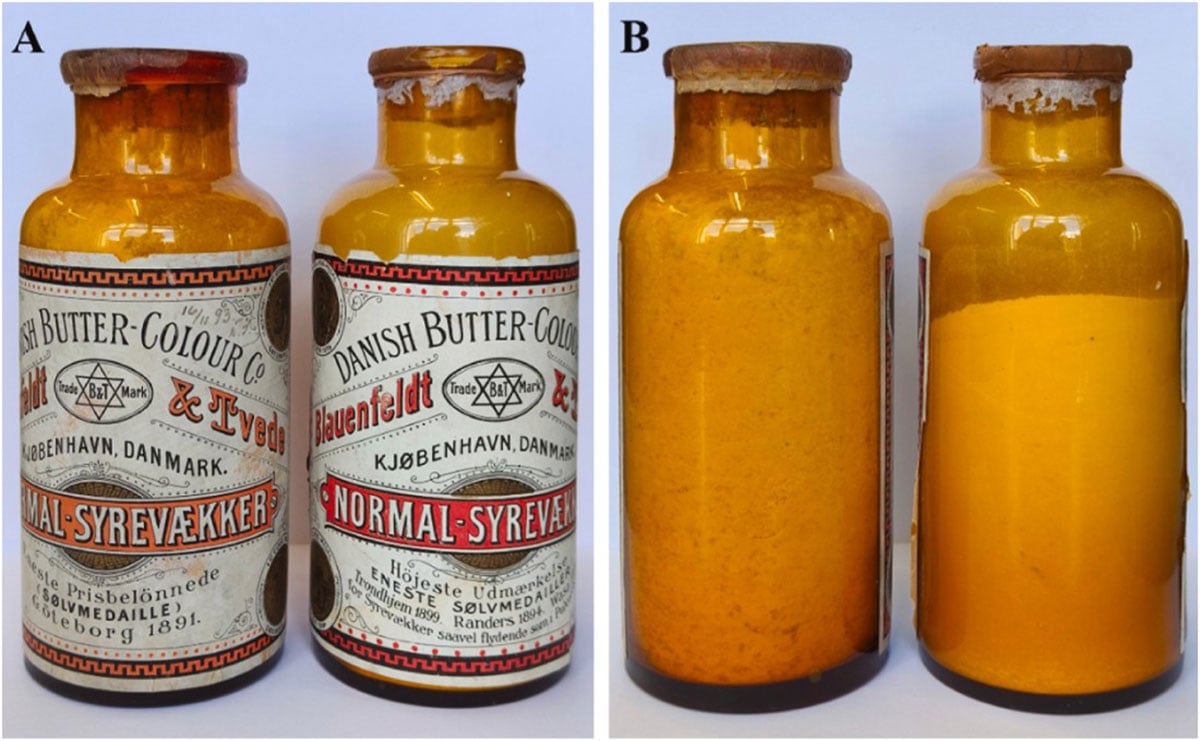

Evidence of this history came to light when researchers stumbled upon two bottles filled with white powder, discovered in a dusty moving box last year. Their labels indicated that they contained cultures of lactic acid bacteria. Untouched since the late 19th century, the bottles had been tucked away beneath the greenhouses on Rolighedsvej, near the former Agricultural College in Frederiksberg.

Using advanced DNA sequencing, scientists were able to analyze the powder in detail and compare it with bacterial DNA databases. This was an uncertain endeavor, as organic material typically degrades with age, making recovery of genetic information difficult.

The results confirmed that the powder held remnants of lactic acid bacteria once purchased by Danish dairies. These cultures were added to cheese, milk, and butter after pasteurization, reintroducing beneficial bacteria once the heat treatment had eliminated undesirable microbes.

“It was like opening a kind of microbiological relic. The fact that we were able to extract genetic information from bacteria used in Danish butter production 130 years ago was far more than we had dared to hope for,” says microbiologist Jørgen Leisner from the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences.

Hygiene conditions were different

In the bottles, the researchers found DNA from Lactococcus cremoris—a lactic acid bacterium that is still used to acidify milk in modern dairy production. The analysis also revealed that the bacterial culture had genes to produce diacetyl—a flavor compound that gives a characteristic butter aroma.

“This shows that even back then, they had bacteria with precisely the properties that are desirable in the fermented milk products we have today,” says Professor Dennis Sandris Nielsen from the Department of Food Science.

On a more serious note, the analyses also showed that the bottles were heavily contaminated with Cutibacterium acnes – a common skin bacterium known to cause acne.

“The acne bacterium has a stronger cell wall than many other bacteria, as it needs to be able to survive a hostile environment on the skin. Therefore, it also breaks down more slowly, which enabled us to find its DNA in large quantities after 130 years in the bottles,” explains Jørgen Leisner.

In addition, the bottles also contained DNA traces of potentially pathogenic bacteria, including the staphylococcus bacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, and Vibrio furnissii. The latter is known to cause stomach infections when eating shellfish that has not been cooked properly.

“Overall, the contents of the bottles testify to the standardization of a dairy product that every farming family used to make themselves in a jar of sour milk kept close to the stove. But it also shows that hygiene conditions were still different from those we have today,” says anthropologist Nathalia Brichet from the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, who is co-author of the study.

Unique insight into Denmark’s butter adventure

At the end of the 19th century, Denmark began exporting butter to England on a large scale. This placed new demands on consistency and hygiene in production. And here, pasteurization became the solution. But because heat treatment also kills natural bacteria, there was a need to add bacterial cultures—also called starter cultures—and thus began Denmark’s industrial adventure.

“The starter culture became the key to standardized butter production. It was no longer possible for each dairy to ferment in its own way—it was necessary to ensure that the products tasted the same, regardless of where in the country the butter was made. The starter culture made the taste reproducible,” explains Jørgen Leisner.

The discovery also shows how close collaboration between researchers, industry, and agriculture laid the foundation for Danish food exports. Companies such as Blauenfeldt & Tvede and Christian Hansen emerged during this period and laid the foundation for today’s food giants.

“It’s easy to forget the enormous scientific work it takes—and took—to produce standardized, food-safe, and sought-after dairy products for export. This didn’t just happen by itself, but is the result of technological advances and innovation dating back a long time. This research gives us an insight into a time when Danish dairy production became a global commodity,” concludes Nathalia Brichet.

Reference: “Metagenomic analysis of 130 years old Danish starter culture material including sequence analysis of the genome of a Lactococcus cremoris starter” by Pablo Atienza López, Taya Tang, Bashir Aideh, Nilay Büdeyri Gökgöz, Nathalia Brichet, Dennis Sandris Nielsen, Jørgen J. Leisner and Lukasz Krych, 2 April 2025, International Dairy Journal.

DOI: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2025.106258

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Source link