Context

The Global South is urbanizing at an unprecedented rate, creating an urgent demand for rapid expansion of infrastructure, services, and economic opportunities. However, many low-income countries face acute resource constraints that hinder their ability to keep pace with this growth22,23. By 2050, an estimated two-thirds of the global population is expected to reside in urban areas, with much of this growth occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)24. Historically, this rapid urbanization has led to the proliferation of informal settlements within these nations. Access to reliable energy, effective waste management systems, and modern water and sanitation services remains very low in some cities in the Global South25,26. These infrastructure deficiencies pose serious health and environmental risks and exacerbate social inequalities and unrest27. In response to these systemic gaps, informal solutions, such as plastic waste burning, have emerged as a means to address the lack of proper waste management and energy access needs28.

Continued use of traditional stoves enables the burning of waste plastic as fuel. Low-income households migrating to informal settlements to escape high rental costs often face barriers in accessing affordable, clean fuels. Moreover, the rapid growth of densely populated settlements intensifies pressure on local forests and other natural resources, driving up the costs of traditional fuels such as wood and charcoal29. One notable consequence is the increased scarcity of biomass fuels, which has become a contributing factor to accelerating the energy transition in many urban environments. This transition is occurring at a highly unequal rate30. However, it is leaving lower socioeconomic status and marginalized communities behind31, and exacerbating energy insecurity for those least able to afford clean commercial fuels10 and forcing them to look for no- or low-cost fuels, which can include unmanaged solid waste.

As a readily available waste product that combusts easily, plastic is a potentially attractive fuel source for low-income households struggling to meet their energy needs. Plastic waste is difficult to manage as it does not decay like organic waste, nor does it have the resale value that metals have; this makes burning or incineration a widely accepted method of management1,28. Unfortunately, burning waste, particularly plastic waste, releases many harmful toxins that negatively affect household environments and spill over to contribute to poor urban air quality20,32. The harms from plastic burning extend beyond direct human exposure to toxic emissions via inhalation. Secondary impacts, including ingestion of contaminated food, documented in environmental analyses, underscore additional risks associated with plastic combustion33. For example, chicken egg samples from an electronic waste site in Ghana, where plastic and cables were burnt in an open fire, have been found to contain toxins34,35. Additionally, the technologies and tools used to burn plastic waste, along with how individuals interact with these tools, likely play a critical role in influencing the environmental and health impacts of this practice, both within households and across broader communities.

While systematic evidence on the prevalence and extent of plastic waste burning as a household fuel remains limited, anecdotal and localized studies indicate that the practice could be widespread15,16,36. Systematic and comprehensive data gathering on this topic, including results from this survey, is needed to advance understanding of the complex dynamics of plastic waste burning and to inform policies and targeted programs aimed at mitigating its risks21.

Survey results

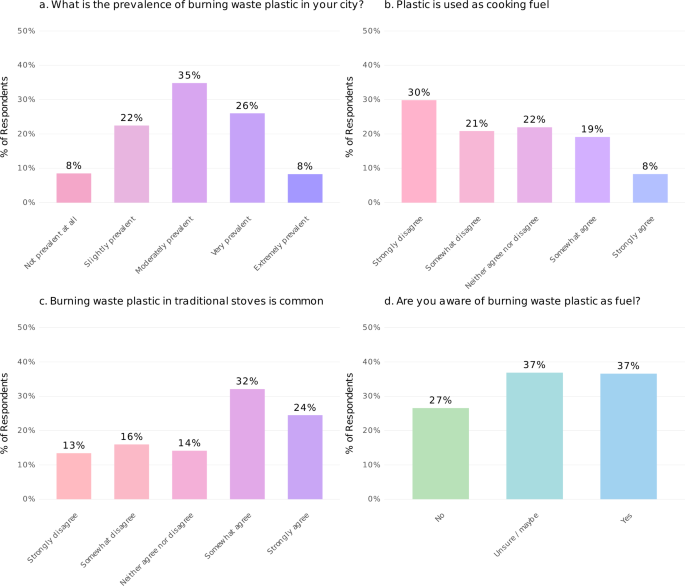

Responses were obtained from 1018 key informants familiar with the context of their cities were analysed in this study; see Table 1 for sample summary statistics (and “Methods” for additional details). Respondents were asked about the general prevalence of plastic waste burning in their city. Among 931 responses for this question, 22% indicated that plastic burning was slightly prevalent, 35% reported it was moderately prevalent, 26% responded it was very prevalent, and 8% described it as extremely prevalent (Fig. 1a).

a Reported prevalence of burning plastic waste; b Agreement that plastic waste is used as a cooking fuel; c Agreement that plastic waste is commonly burned in traditional stoves; and d Awareness of burning plastic waste as a fuel. The numbers above the bars indicate the percentages for each response. Totals may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Respondents were also asked about the use of plastic waste as a household fuel through three questions. Among the 989 respondents who answered a first question on burning of plastic cooking fuel as a replacement for other fuels, 19% somewhat agreed and 8% strongly agreed, indicating notable agreement to this practice (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, 22% neither agreed nor disagreed, while the remaining respondents either disagreed (21%) or strongly disagreed (30%) with the statement.

In a second question, 32% of participants somewhat agreed, and 24% strongly agreed that burning plastic waste in traditional stoves is common practice (N = 985). By contrast, 16% disagreed, and 13% strongly disagreed (Fig. 1c). These responses suggest a higher prevalence of plastic waste burning compared to the first survey question, which may indicate that plastic burning is used primarily to manage household plastic waste, rather than as a primary or preferred energy source for cooking.

The third question asked respondents whether they were aware that plastic waste was used as a household fuel in their cities, with three response options: yes, unsure and no. Affirmative answers to this question appear to lie between those on the two other questions: out of 998 respondents who answered the question, 37% reported being aware of this practice, 37% were unsure, and 27% were unaware (Fig. 1d).

The 365 respondents who indicated awareness of plastic waste burning for energy purposes in their city, from the final question ‘Are you aware of burning waste plastic as fuel’, were also asked follow-up questions regarding the specific purpose of this practice. Out of the total respondents, 16% reported burning plastic for at least one purpose, 10% reported using it for two purposes, and 5% for three different purposes.

Nearly half (48%) reported witnessing others burn plastic waste as a cooking fuel, while 14% responded that they had done so themselves. Another 13% indicated they had heard about the practice but had not seen it firsthand (Fig. 2a). Regarding the burning of plastic waste for heating purposes, 37% had seen others doing it, 12% had done it themselves, and 18% had only heard about it being done (Fig. 2b). A smaller proportion of respondents were aware of plastic being burned to prepare cattle feed: 12% had witnessed it, 11% had heard about it, and 4% had engaged in the practice (Fig. 2c). The lower awareness of the latter likely reflects the relatively limited cattle ownership in the urban areas that were the focus of our survey.

Percentage of respondents aware of plastic waste being burnt and used as (a) cooking fuel, (b) heating, (c) heating cattle feed, (d) by mixing with other fuels like firewood, (e) deter pests, (f) fire starter. This is a follow-up question asked only to respondents who indicated they were aware of burning plastic (Fig. 1d) waste as fuel (N = 365). The numbers above the bars indicate the percentages for each response. Totals may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Fuel stacking, the use of multiple fuel types to meet household energy needs, is a well-documented practice in low-income settings37. However, this behavior can contribute to increased toxic emissions, especially when polluting fuels such as plastic are mixed with other materials38. To explore this further, the survey examined the extent to which plastic is combined with other fuels in household fires. Among those aware of plastic burning, 22% reported burning plastic with different fuels, 46% had witnessed this practice, and 14% had heard about it (Fig. 2d). Integrating plastic waste into household fuel use for multiple purposes appears to be relatively common among respondents familiar with plastic combustion.

The survey also investigated whether burning plastic waste is employed to deter pests and insects, as smoke emissions from polluting energy sources are sometimes considered effective in doing so39. While only 6% of respondents reported burning plastic waste for this purpose, 17% had witnessed it, and 19% had heard about it (Fig. 2e). The survey also investigated whether plastic waste is used for lighting fires. The survey found that 38% of respondents had used plastic as a fire starter, 40% had witnessed this use, and 13% had only heard about it (Fig. 2f).

The extent to which plastic waste is used as a household fuel varies by country, with patterns that correlate with regional and national income levels. Figure 3 show the proportion of respondents who agreed that plastic waste is used as a fuel substitute, acknowledged plastic burning to be a common practice, and reported awareness of plastic waste combustion for energy purposes according to country income (Fig. 3a, c) and by region (Fig. 3b, d). The measures were converted from a Likert scale – previously discussed in Fig. 1—to a binary variable indicating some or strong agreement. Plastic waste combustion is more prevalent in low-income countries, except for heating purposes (Fig. 3b), which likely reflects differences in climate. Regional differences are also notable, with respondents in Sub-Saharan Africa reporting a higher prevalence of these practices compared to those in other regions, for all purposes (Fig. 3d). Additionally, the disaggregated data suggest that fuel substitution with plastic (the first measure) may be somewhat over-reported in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and Southeast Asia (SEA). This is indicated by higher rates of agreement (represented by the orange bars) compared to direct awareness of plastic waste combustion for energy needs (green bars).

a Proportion of respondents who somewhat or strongly agree that plastic is burnt as a fuel (blue bar); somewhat or strongly agree that it is common practice to burn plastic waste in traditional stoves (orange bar); and report being aware of burning of plastic as a household fuel (green bar) across LIC = low-income country; LMC = lower-middle-income country; and UMC = upper-middle-income country categories. b Same variables as panel a, by region LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SEA = South Asia SA = South Asia; SAF = Southern Africa; WAF = Western Africa; EAF = Eastern Africa; MAF = Middle Africa. The MAF and LAC numbers are based on responses from a single country in each region, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Peru, respectively. c Proportion of respondents reporting having seen or burnt plastic themselves for various purposes, among those aware of plastic waste burning (the green bars in Panels (a, b)), by country income category and (d) region.

Respondents who reported awareness of burning plastic waste as a household fuel (N = 366) were asked additional questions about the specific types of plastic materials being burned, the product(s) they originated from, and the stoves used for their combustion. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET or PETE) is the most frequently reported type of burned plastic waste, followed by low-density Polyethylene (LDPE). PET and LDPE are common single-use plastics found in beverage bottles (e.g., water and juice bottles) and bags (Fig. 4a). They are the most common plastic materials found in household waste and accumulating in the oceans bordering Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia40,41,42. The third most frequently reported plastic being burned is high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a material frequently used for chemical containers. The fifth most frequently used plastic material is polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is mostly used in plastic plumbing pipes, and is a major cause of dioxin emissions43.

a Mean of the rank value of plastic materials. The y-axis indicates the mean rank value, where 7 is the most frequently burned and 1 is the least frequently burned plastic material (the rank value flipped from the original scale), as reported by those aware of plastic burning for fuel (N = 306). b Relative frequency of plastic products burned for fuel among those aware of plastic burning (N = 318). c Percentage of responses by stove type most commonly used by households to burn plastic (N = 323). A 3-Stone (Three-Stone) stove is a primitive traditional stove where three stones are arranged to support a pot; a mud stove is an enclosed stove built from mud; an improved cooking stove (ICS) is a more efficient, safer and less polluting stove; and a charcoal stove is designed to use charcoal as fuel.

In terms of product origin, nearly two-thirds of respondents reported burning food wrappers, followed by chemical packaging materials such as fertilizers, pesticides, and cleaning liquid containers (Fig. 4b). Food wrappers, made from polypropylene (PP), account for the largest share of waste generation by polymer type14,44,45, and are reported as the most frequently burned plastic product. Other commonly burned plastic items included non-food household plastics like buckets and plastic bags (35%), construction materials such as pipes (32%), and components from tyres and white goods, i.e., household electrical appliances (26%). Traditional cooking stoves such as those using 3-stone and charcoal are among the most widely used stoves for burning plastic waste (Fig. 4c).

Energy consumption is influenced by household socio-demographic characteristics. To better understand the socio-demographic factors associated with burning plastic waste as a fuel, respondents were presented with a set of factors and asked to rate the likelihood that individuals with these characteristics could burn plastic waste as fuel, on a scale from −10 (not likely) to +10 (most likely).

Households that include people with disabilities—with the term ‘disabilities’ left undefined in the survey question—were seen as less likely to burn plastic waste, possibly due to their limitations in collecting plastic waste (Fig. 5a). By contrast, respondents indicated that households in areas excluded from waste management services could be most likely to burn plastic waste, followed by those experiencing poverty and those living in informal settlements. Additionally, households with members working at waste sites, such as waste pickers, were perceived to be more likely to burn plastic waste as fuel. The regionally disaggregated results highlight variations in the perceptions of these socio-demographic correlates with the burning of plastic waste as fuel.

Overall (bar graph) and disaggregated by region (heatmap). a Percentage of respondents who believe burning plastic waste is positively associated with various socio-demographic groups. Responses were measured using a scale ranging from −10 to +10 (where −10 indicates a strong and negative association, i.e., low likelihood of burning plastic waste as household fuel; and +10 indicates a strong and positive association, i.e., high likelihood of burning plastic waste), converted binary variable that takes value of 1 for respondents with positive response (1 to 10) otherwise zero. b Percentage of respondents who somewhat agree or strongly agree about the reasons for burning plastic waste overall (bar graph) and disaggregated by region (heatmap). Responses measured using a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree rescaled as a binary that takes the value of 1 for respondents who select somewhat agree or strongly agree, otherwise 0. LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SEA = South Asia SA = South Asia; SAF = Southern Africa; WAF = Western Africa; EAF = Eastern Africa; MAF = Middle Africa. The MAF and LAC numbers are based on responses from a single country in each region, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Peru, respectively.

In compact neighborhoods lacking waste management services, some residents may be concerned about the open burning of plastic waste. In such instances, households may choose to burn plastic waste in their traditional indoor stoves to avoid drawing concern. Respondents were asked to indicate why households might burn plastic waste as a household fuel, based on their levels of agreement with the question “Below are some reasons why households might burn plastic waste for household fuel. Please rate the extent to which you agree with these statements”. Respondents indicated strong agreement that a lack of awareness of the health impacts of burning plastic was a reason for burning plastic waste, a finding that is also consistent across regions (Fig. 5b). The second highest level of agreement was for two other reasons: to “manage waste” and cope with “expensive clean fuel”. Respondents expressed lower agreement on the role of low availability of traditional fuels as a reason for burning plastic. They generally disagreed that plastic is a versatile fuel or that the burning of plastic waste as a fuel is socially acceptable. In the regionally disaggregated results, respondents from Latin America and the Caribbean tended to highlight a lack of waste management and a lack of awareness as the main reasons for burning plastic. In contrast, respondents from Asia, Southern Africa, and West Africa also tended to emphasize the role played by the low availability of traditional fuels.

Awareness of these risks was assessed, for four different types of risks, based on agreement with the statement “What do you believe are the major risks of burning plastic for households?” (the level of agreement was recorded on a Likert scale ranging from extremely unlikely (1) to extremely likely (5)). Respondents strongly agreed on the risks and impacts of toxic emissions inhalation, fire hazards, and food contamination, with results also consistent across regions (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). While a detailed understanding of the risks from burning plastic waste to the environment and human health is limited, there was a high degree of awareness that these impacts could be harmful, with both direct and indirect consequences.

More specifically, out of 936 respondents, 40% indicated that they thought burning plastic was extremely likely to contribute to fire hazards, and 40% stated this was somewhat likely. Regarding the risk of toxic emissions and air pollution from burning plastic, 62% indicated that this was extremely likely, and 26% indicated that it was somewhat likely. Roughly 6 in 10 respondents thought it was extremely likely that toxic chemicals from burning plastic waste could contaminate food and water, while 29% indicated it was somewhat likely.

Given the higher exposure rates for household members who spend more time indoors, respondents were also asked to indicate the likelihood of greater risks of exposure for females, children, people living with disabilities, and senior citizens. Forty-six percent of respondents reported that increased risk of exposure was extremely likely, and 34% reported that it was somewhat likely (See Supplementary Fig. 1).

Energy use, including the burning of plastic waste, is contextual, and addressing energy poverty requires localized solutions that are appropriate to their specific context46,47. Respondents were asked to rank what they believed was the most important solution to the issue of burning plastic waste as household fuel in their city. As shown in Fig. 6, the average rankings (where lower values indicate higher effectiveness) suggest that improved and expanded solid waste management services for informal settlements (waste management) are seen as the most effective solution to the problem, followed by increased access to clean energy technologies and raising awareness about the negative effects of burning plastics for fuel. Bans on the use of plastic were also ranked as having high importance, whereas the supply of traditional fuels and the conversion of plastic to a safe fuel were among the lower-ranked solutions. There are regional variations in perceptions of these solutions. Respondents from South Asia and Southern Africa ranked a ban on plastic use as the most effective solution, possibly due to plastic ban policies. Respondents in Latin America and the Caribbean considered waste management and clean cooking to be more important than awareness. In East and Central Africa, access to clean energy was ranked as the most important solution among low-income households. While these results are subjective and may be subject to differing interpretations of this question, the result underscores the need for contextual strategies.

Mean value for the ranked relative importance of possible solutions. a Energy access-related solutions for the whole sample, and by region. b Waste management and awareness-related solutions for the whole sample, and by region. Responses were ranked in order of importance (1 = the most effective solution and 7 = the least effective solution) (N = 832). LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SEA = South Asia SA = South Asia; SAF = Southern Africa; WAF = Western Africa; EAF = Eastern Africa; MAF = Middle Africa. The MAF and LAC numbers are based on responses from a single country, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Peru, respectively.

Correlational insights into plastic burning practices

Individuals active in socially engaged professions, e.g., community-based organization personnel, community workers, or teachers, were significantly more likely to agree that plastic waste burning occurs in their communities (p = 0.003). However, they did not report direct awareness of others or themselves engaging in it (Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 4). Respondents who perceived municipal solid waste management fees as unaffordable (p < 0.007, Column 1; p < 0.019, Column 2) were also more likely to report that plastic burning occurs and that they engage in it. A perception of clean fuels as expensive was also positively correlated with these outcomes (p < 0.000, Column 1; p < 0.000, Column 2; p < 0.004, Column 3). Meanwhile, city-level factors such as quantities of plastic waste (p < 0.023, Column 2; p < 0.008, Column 3), and population without waste collection services (p < 0.000, Column 2; p < 0.000, Column 3) were positively correlated with direct awareness of others’ or individuals’ own plastic waste burning for energy purposes. The insignificant correlations between the volume of mismanaged plastic waste in the city and the population without waste collection, on one hand, and respondents’ general agreement that plastic is burned for energy purposes, on the other, may be related to overreporting of general awareness compared to direct awareness.

Agree (green) shows the odds ratios from the logistic regression for respondents’ agreement on the use of plastic as fuel. The dependent variable is binary, converted to indicate if respondents somewhat or strongly agreed with the statements “It is common practice to burn plastic waste (like polythene bags) in the fire of traditional stoves,” as 1, and otherwise 0. Aware (purple) presents the odds ratios for the dependent variable for awareness of plastic waste burning based on the third question in Fig. 1, which takes the value of 1 if respondents answered ‘yes’ to the question: “Are you aware of households burning plastic waste as fuel to meet their household energy needs (e.g., fire starters and for cooking and heating)?”, otherwise 0. Used (lavender) shows the odds ratio of respondents’ own burning plastic waste for various purposes, where the dependent variable takes a value of 1 if respondents reported burning plastic themselves (yes, I have done it) for cooking, heating, mixed energy use, preparing cattle feed, deterring pests, or starting fires. To improve the readability of coefficient estimates and odds ratios in the coefficient plot, variables measured in percentages (no waste collection and basic sanitation services) and grams (total waste and plastic waste generation) were rescaled (robust 95% confidence interval in bar). Errors are clustered at the city level. See Supplementary Table 3 for summary statistics of variables and Supplementary Table 4 for full results).

Fuel supply factors (availability and accessibility to clean fuels), urban waste management (linked to economic development), and demand drivers (e.g., higher development and income levels reducing reliance on polluting fuels) all influence plastic burning practices. Interpreted together, they highlight the link between inadequate waste management systems, expensive clean cooking fuel, and reliance on plastic waste as a household fuel. A perception that waste management services and clean fuels are expensive highlights and reiterates the vital importance of affordability. Reliance on traditional fuels and stoves also contributes to household vulnerability, which in turn facilitates the domestic burning of plastic as a fuel. While open burning of plastic waste is a well-known and common waste management strategy in many cities in the Global South, the widespread prevalence and correlates of domestic burning of these materials have not previously been documented. These results reinforce the importance of cross-cutting programs to improve waste management systems (SDG11.6) and expand access to affordable, clean cooking solutions to low-income households (SDG7).

Source link